Instituting Beyond Human

What is the purpose of archiving the past when the future is bound to mass extinction? This is one of the most pressing questions that museums, public art collections, and all of us working in or with cultural institutions are facing. We keep being reminded of it, whether by the climate activists who defaced several paintings with soup and other fluids, or by nature itself when, for instance, the LA fires surrounded the Getty.

Over the years, foodculture days has gained a stable place in the cultural ecosystem of Switzerland. This entails a necessary reflection on the previous chapters, but also a commitment to the future. In October last year, I was invited to join of a small group of land, food and art practitioners to discuss possible directions of transformation, imagination, critique and improvement for the organization. These three lovely days were spent sharing experiences and speculating around questions like: What can the institution do? Who gets to be part of food and culture? And, following up on threads that we started weaving with Juliane Foronda in the workshop ‘Comfort as Labor’¹, during the 2023 edition of the biennale, what relationships do we want to sustain when we talk about sustainability?

As an extended contribution to this ongoing debate, I will discuss the Katzenwedelwiese, a collective artwork that involves many human and other-than-human collaborators. To complement this essay, an assemblage of visual artefacts, songs, recipes, and memories has been collected by Barbara Kiolbassa who co-initiated the project with me and Bettina Korintenberg in 2019 at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe.

The ZKM is an institution and a passionate community known for its commitment to the preservation of early media art and digital works. Invited to take part in the three-year exhibition project Critical Zones curated by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel², I proposed to expand that conservation expertise to a living ecosystem: an abandoned orchard meadow neighbouring the museum going by the local name of Katzenwedelwiese (literally “cat’s tail field”, in reference to the topographic shape of the river that delineates the northern edge of the meadow).

Winter pruning on the Katzenwedelwiese. 2022. Photo: Elias Sibert.

The agroecological tradition of orchard meadows is well-known in Switzerland and South Germany, where they have been granted the UNESCO status of intangible heritage for their cultural and ecological value³. In addition to growing organic, sustainable food, often from vernacular or ancient fruit varieties, they double as biodiversity hotspots that shelter pollinators, wildflower species and small animals. Because maintenance relies on long, non-mechanizable and strenuous labour like the mowing of wildflower meadows and the pruning of large trees⁴, these “naturecultures” are endangered; it is estimated they will entirely disappear by 2050⁵. The production of fruit (and cider, honey, animal grazing, etc.) is not the only objective, but rather one function of a complex food system that delivers many ecological services supporting various forms of symbiotic cooperations: the vast wildflowers meadows shelter small mammals and feed specific insects that in turn pollinate the fruit trees, which also provide food for birds and animals.

With the help of the city of Karlsruhe’s property department, we discovered the Katzenwedelwiese just 1km south of the ZKM, at the border of the neighbourhoods of Bulach and Beiertal. This small orchard was unmaintained since years and left in a state of neglect. The institution’s commitment to the regeneration and care labour for the orchard was established in a contract with the city, which owns the land. The ZKM being specially devoted to preserving “endangered” early media art, thanks to a community of artists, technologists, hackers, that looks after works from the collection and maintains obsolete technology, I was interested in the contrast between the high technological intensity of these maintenance practices, and the high ecological intensity of orchard farming. Orchard meadows are ecosystems shaped by human intervention (through design, genetic selection of species, etc.) that require constant human maintenance to keep with ecological wellbeing.

For Martin Flinspach, one of the founders of Karlsruhe’s Orchard Initiative⁶, orchard meadows blur the boundaries between art and cultivation, but also between human and non-human authorship:

When you look at the shape of a tree, like a 120 years old pear tree, when you look at the form… the tree itself is a work of art. If you contemplate an orchard, you see trees with a twisted trunk, or a particular crown, and you see them as nature’s artwork. They are impressive forms. There is such an intensity of form in the landscape, that comes from those fruit trees. That is a work of nature’s art. There is also a whole culture behind it, of the plant, of the care, of the different directions in which a tree can grow… That is nature labour, but also art labour.

(Interview Dr. Martin Flinspach, 11.02.2020)

Tree pruning course. 2020. Photo: Elias Sibert.

In a way, the project explores whether the conservation processes inherited from the object-centred history of museums can be hacked to support new more-than-human collectives. If we consider seriously the claim that “nature” has entered the field of “culture” production, we then need to put the practical tools of institutional modernity to new uses, working with and for other-than-humans.

While it would by far exceed the scope of this contribution, it would be interesting to develop a speculative analysis of the confluences between the fields of museum conservation and nature conservation throughout modernity, following up on Tony Bennet’s seminal essay “The exhibitionary complex”⁷ . Reading the history of museological practices in conjunction with emerging environmental policies of biopower like managing wilderness, categorizing species, creating reserves, etc., would give an interesting insight into how the concern with keeping things the same has informed the control over nature and culture and the desire to maintain cultural artifacts and ecosystems in timeless, idealized states. From the feminist critique of maintenance (what is cared for? who cares for it?) in both the cultural and environmental realms, to recent academic work such as Fernando Domínguez Rubio’s research on the museum infrastructure, which he compares to an agro-industrial supply chains that support the modern food industry⁸, it seems relevant to understand critically art and environmental conservation through a transverse, ecological analysis.

The Katzenwedelwiese directly contributes to the preservation of biodiversity in the city. It is home to bees, flowering plants, beetles, insects, birds, frogs, butterflies, bats, mushrooms, three plum trees, seven apple trees (Oberländer Himbeerapfel, Brettacher Apfel, Rheinischer Bohnapfel, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Apfel), two cherry trees, one pear tree, one mirabelle plum tree, and many more. New trees have been planted. Twice a year, at the end of winter and the beginning of autumn, the trees are pruned and the meadow is mowed for the growth of wildflowers. We feed the mowed grass to the cows of a nearby farms, harvest the fruits, produce preserves, jams and “schnapps” (liquor).

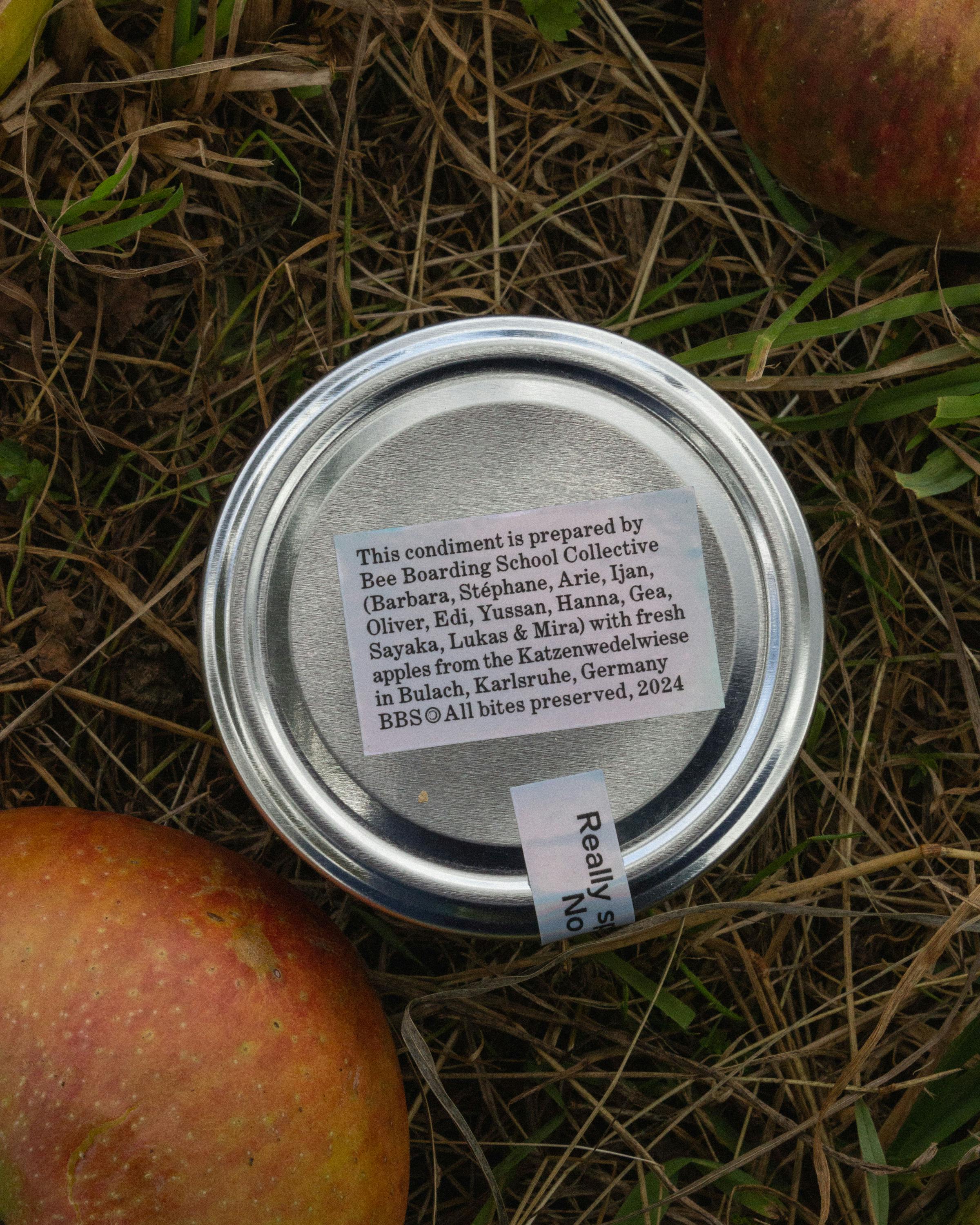

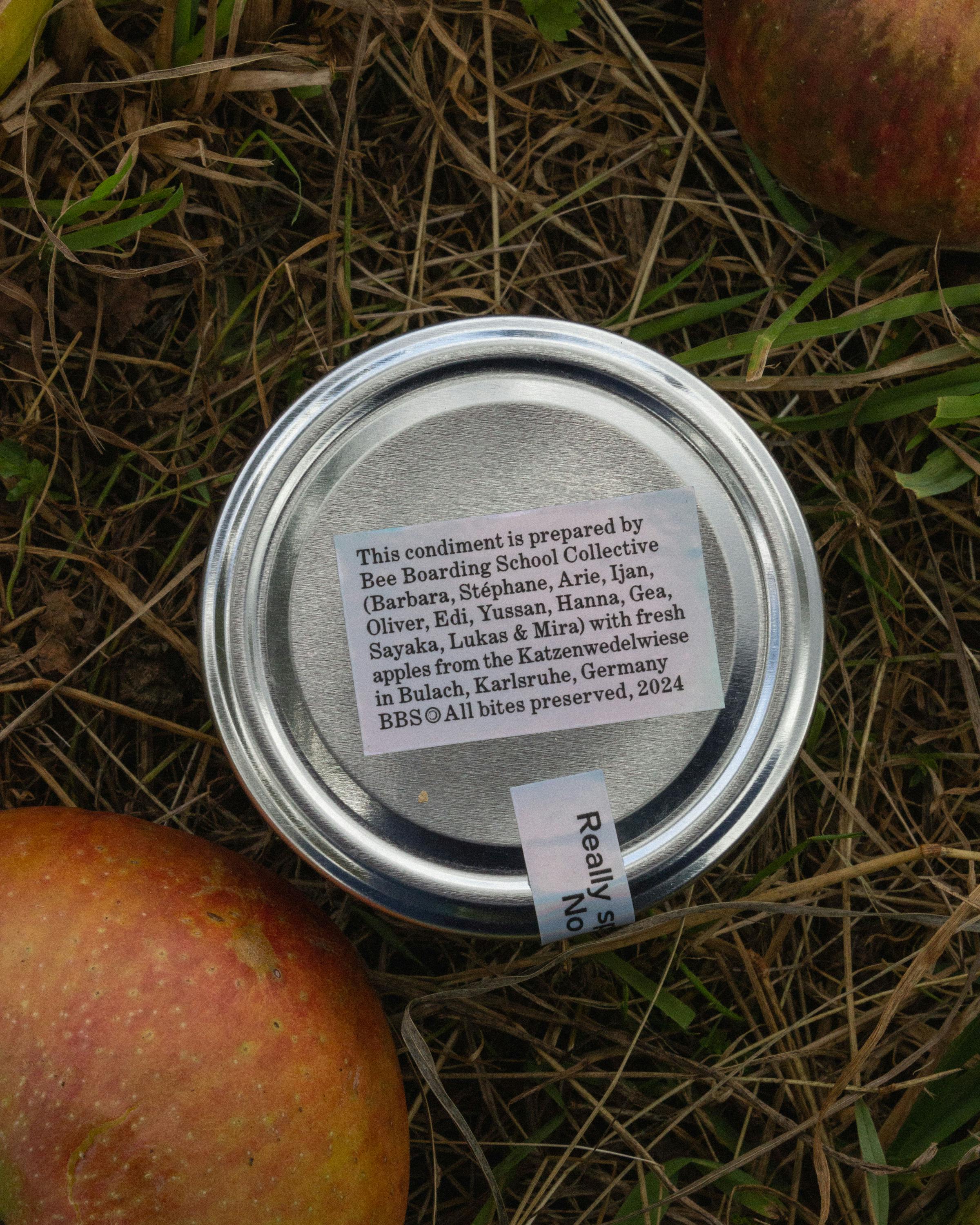

Karinding Workshop by Vincent Rumahloine and Reksi Muhamed Sidik. Photo: ZKM.

Over the last 5 years, the ZKM teams were joined in the maintenance work by a growing network of local friends, allies, neighbours, artists, gardeners, beekeepers. This relies on a long learning process, as we follow regular horticultural trainings by experts from Karlsruhe’s Orchard Initiative. Culinary production is integral to the project. We have created preserves, jams, and schnapps, some of which have travelled around the world to other sites of artistic expression as vessels of sharing and solidarity. These food practices foster community engagement through programs like the Bee Boarding School in 2024, which also highlight the importance of sustainable food systems that support local biodiversity. Just as carefully crafted preserves require attention to detail and patience to ensure their longevity, the maintenance of the orchard demands meticulous care to preserve its ecological balance. The analogy extends beyond the physical act of preservation; it also underscores the community's effort in participating fully in this natureculture meshwork⁹. Preserving is always intentional: preserves are made to pass the winter, to save the surplus, to prepare for days of lesser abundance. Preserving connects past, present, and future, much like the orchard project itself, an effort to make shelter for endangered becomings.

The restoration of the orchard meadow opens a deleuzian “line of flight” out of the white cube, rather than serving as a site from which artistic material can be extracted and brought back into the spectacle of the museum. Caring becomes more than conserving past heritage and organized collections. It alters, unsettles, and expands what the institution does and means. From “archive of the commons”¹⁰, not only is the museum’s concern shifting towards more-than-human commons; it also becomes exposed to the ontological instability, uncertainty and indeterminacy at work in living ecosystems. The future institution, which we tried to imagine as we met to discuss the next steps for Food Culture Days, will support a concrete experience of solidarity and longevity, where preservation is not about control but freedom and difference.

Stéphane V. Bottéro

Stéphane V. Bottéro is an artist, ecologist and sometimes curator working at the intersection of social practice, installation, writing, and gardening. With a background in environmental science, he is interested in the entanglements of community, materiality, body and place. Based on site-specific research and durational interventions, his practice explores pedagogies of repairing. He co-initiated the collaborative platform The School of Mutants in Dakar in 2018. In the framework of the exhibition Critical Zones at ZKM, he initiated the Katzenwedelwiese project in Karlsruhe, a collaborative socio-ecological artwork and orchard meadow restoration effort that has developed continuously since 2019. His work has been exhibited at biennales, museums, and festivals, including: ZKM, Karlsruhe; 4th Autostrada Biennale; Centre Pompidou Metz; 12th Berlin Biennale; 14th Dakar Biennale; RAW Material Company, Dakar; 12th Taipei Biennial; 7th Oslo Triennale; Le Lieu Unique, Nantes; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Sheffield DocFest. He has lectured and taught at Leeds School of Art, HEAD Geneva, Ensad Paris, HKB Bern, St Lukas Antwerp.

¹: See https://foodculturedays.com/en/program/2023/frca/ ²: Curated by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, the project Critical Zones sought to use the ZKM as an “observatory of […] the new forms of citizenship and new types of attention and care for life forms required to generate a common ground” (Latour & Weibel, 2020), emphasizing how the Earth has entered human politics. It included a seminar, an exhibition, a catalogue, and an abundant program of events between 2019 and 2021.

³: UNESCO Deutschland. (2021). Streuobstanbau. Retrieved from https://www.unesco.de/staette/streuobstanbau/

⁴: Hammel, K., & Arnold, T. (2012). Understanding the loss of traditional agricultural systems: A case study of orchard meadows in Germany. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 2(4), 119-136.

⁵: Mundinger, B. (2022). Paradiese aus zweiter Hand: bedrohte Streuobstwiesen im Ried. Geroldsecker Land, 64, 109-129.

⁶: See https://streuobstinitiative.de

⁷: Bennett, T. (1988). The Exhibitionary Complex. New Formations, No. 4, Spring.

⁸: Rubio, F. D. (2020). Still life: Ecologies of the modern imagination at the art museum. University of Chicago Press.

⁹: About natureculture, see Haraway, D. J. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge. About meshwork, see Ingold, T. (2015). The life of lines. Routledge.

¹⁰: Bishop, C. (2013). Radical museology, or, what's contemporary in museums of contemporary art? Koenig Books.

Instituting Beyond Human

What is the purpose of archiving the past when the future is bound to mass extinction? This is one of the most pressing questions that museums, public art collections, and all of us working in or with cultural institutions are facing. We keep being reminded of it, whether by the climate activists who defaced several paintings with soup and other fluids, or by nature itself when, for instance, the LA fires surrounded the Getty.

Over the years, foodculture days has gained a stable place in the cultural ecosystem of Switzerland. This entails a necessary reflection on the previous chapters, but also a commitment to the future. In October last year, I was invited to join of a small group of land, food and art practitioners to discuss possible directions of transformation, imagination, critique and improvement for the organization. These three lovely days were spent sharing experiences and speculating around questions like: What can the institution do? Who gets to be part of food and culture? And, following up on threads that we started weaving with Juliane Foronda in the workshop ‘Comfort as Labor’¹, during the 2023 edition of the biennale, what relationships do we want to sustain when we talk about sustainability?

As an extended contribution to this ongoing debate, I will discuss the Katzenwedelwiese, a collective artwork that involves many human and other-than-human collaborators. To complement this essay, an assemblage of visual artefacts, songs, recipes, and memories has been collected by Barbara Kiolbassa who co-initiated the project with me and Bettina Korintenberg in 2019 at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe.

The ZKM is an institution and a passionate community known for its commitment to the preservation of early media art and digital works. Invited to take part in the three-year exhibition project Critical Zones curated by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel², I proposed to expand that conservation expertise to a living ecosystem: an abandoned orchard meadow neighbouring the museum going by the local name of Katzenwedelwiese (literally “cat’s tail field”, in reference to the topographic shape of the river that delineates the northern edge of the meadow).

Winter pruning on the Katzenwedelwiese. 2022. Photo: Elias Sibert.

The agroecological tradition of orchard meadows is well-known in Switzerland and South Germany, where they have been granted the UNESCO status of intangible heritage for their cultural and ecological value³. In addition to growing organic, sustainable food, often from vernacular or ancient fruit varieties, they double as biodiversity hotspots that shelter pollinators, wildflower species and small animals. Because maintenance relies on long, non-mechanizable and strenuous labour like the mowing of wildflower meadows and the pruning of large trees⁴, these “naturecultures” are endangered; it is estimated they will entirely disappear by 2050⁵. The production of fruit (and cider, honey, animal grazing, etc.) is not the only objective, but rather one function of a complex food system that delivers many ecological services supporting various forms of symbiotic cooperations: the vast wildflowers meadows shelter small mammals and feed specific insects that in turn pollinate the fruit trees, which also provide food for birds and animals.

With the help of the city of Karlsruhe’s property department, we discovered the Katzenwedelwiese just 1km south of the ZKM, at the border of the neighbourhoods of Bulach and Beiertal. This small orchard was unmaintained since years and left in a state of neglect. The institution’s commitment to the regeneration and care labour for the orchard was established in a contract with the city, which owns the land. The ZKM being specially devoted to preserving “endangered” early media art, thanks to a community of artists, technologists, hackers, that looks after works from the collection and maintains obsolete technology, I was interested in the contrast between the high technological intensity of these maintenance practices, and the high ecological intensity of orchard farming. Orchard meadows are ecosystems shaped by human intervention (through design, genetic selection of species, etc.) that require constant human maintenance to keep with ecological wellbeing.

For Martin Flinspach, one of the founders of Karlsruhe’s Orchard Initiative⁶, orchard meadows blur the boundaries between art and cultivation, but also between human and non-human authorship:

When you look at the shape of a tree, like a 120 years old pear tree, when you look at the form… the tree itself is a work of art. If you contemplate an orchard, you see trees with a twisted trunk, or a particular crown, and you see them as nature’s artwork. They are impressive forms. There is such an intensity of form in the landscape, that comes from those fruit trees. That is a work of nature’s art. There is also a whole culture behind it, of the plant, of the care, of the different directions in which a tree can grow… That is nature labour, but also art labour.

(Interview Dr. Martin Flinspach, 11.02.2020)

Tree pruning course. 2020. Photo: Elias Sibert.

In a way, the project explores whether the conservation processes inherited from the object-centred history of museums can be hacked to support new more-than-human collectives. If we consider seriously the claim that “nature” has entered the field of “culture” production, we then need to put the practical tools of institutional modernity to new uses, working with and for other-than-humans.

While it would by far exceed the scope of this contribution, it would be interesting to develop a speculative analysis of the confluences between the fields of museum conservation and nature conservation throughout modernity, following up on Tony Bennet’s seminal essay “The exhibitionary complex”⁷ . Reading the history of museological practices in conjunction with emerging environmental policies of biopower like managing wilderness, categorizing species, creating reserves, etc., would give an interesting insight into how the concern with keeping things the same has informed the control over nature and culture and the desire to maintain cultural artifacts and ecosystems in timeless, idealized states. From the feminist critique of maintenance (what is cared for? who cares for it?) in both the cultural and environmental realms, to recent academic work such as Fernando Domínguez Rubio’s research on the museum infrastructure, which he compares to an agro-industrial supply chains that support the modern food industry⁸, it seems relevant to understand critically art and environmental conservation through a transverse, ecological analysis.

The Katzenwedelwiese directly contributes to the preservation of biodiversity in the city. It is home to bees, flowering plants, beetles, insects, birds, frogs, butterflies, bats, mushrooms, three plum trees, seven apple trees (Oberländer Himbeerapfel, Brettacher Apfel, Rheinischer Bohnapfel, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Apfel), two cherry trees, one pear tree, one mirabelle plum tree, and many more. New trees have been planted. Twice a year, at the end of winter and the beginning of autumn, the trees are pruned and the meadow is mowed for the growth of wildflowers. We feed the mowed grass to the cows of a nearby farms, harvest the fruits, produce preserves, jams and “schnapps” (liquor).

Karinding Workshop by Vincent Rumahloine and Reksi Muhamed Sidik. Photo: ZKM.

Over the last 5 years, the ZKM teams were joined in the maintenance work by a growing network of local friends, allies, neighbours, artists, gardeners, beekeepers. This relies on a long learning process, as we follow regular horticultural trainings by experts from Karlsruhe’s Orchard Initiative. Culinary production is integral to the project. We have created preserves, jams, and schnapps, some of which have travelled around the world to other sites of artistic expression as vessels of sharing and solidarity. These food practices foster community engagement through programs like the Bee Boarding School in 2024, which also highlight the importance of sustainable food systems that support local biodiversity. Just as carefully crafted preserves require attention to detail and patience to ensure their longevity, the maintenance of the orchard demands meticulous care to preserve its ecological balance. The analogy extends beyond the physical act of preservation; it also underscores the community's effort in participating fully in this natureculture meshwork⁹. Preserving is always intentional: preserves are made to pass the winter, to save the surplus, to prepare for days of lesser abundance. Preserving connects past, present, and future, much like the orchard project itself, an effort to make shelter for endangered becomings.

The restoration of the orchard meadow opens a deleuzian “line of flight” out of the white cube, rather than serving as a site from which artistic material can be extracted and brought back into the spectacle of the museum. Caring becomes more than conserving past heritage and organized collections. It alters, unsettles, and expands what the institution does and means. From “archive of the commons”¹⁰, not only is the museum’s concern shifting towards more-than-human commons; it also becomes exposed to the ontological instability, uncertainty and indeterminacy at work in living ecosystems. The future institution, which we tried to imagine as we met to discuss the next steps for Food Culture Days, will support a concrete experience of solidarity and longevity, where preservation is not about control but freedom and difference.

Stéphane V. Bottéro

Stéphane V. Bottéro is an artist, ecologist and sometimes curator working at the intersection of social practice, installation, writing, and gardening. With a background in environmental science, he is interested in the entanglements of community, materiality, body and place. Based on site-specific research and durational interventions, his practice explores pedagogies of repairing. He co-initiated the collaborative platform The School of Mutants in Dakar in 2018. In the framework of the exhibition Critical Zones at ZKM, he initiated the Katzenwedelwiese project in Karlsruhe, a collaborative socio-ecological artwork and orchard meadow restoration effort that has developed continuously since 2019. His work has been exhibited at biennales, museums, and festivals, including: ZKM, Karlsruhe; 4th Autostrada Biennale; Centre Pompidou Metz; 12th Berlin Biennale; 14th Dakar Biennale; RAW Material Company, Dakar; 12th Taipei Biennial; 7th Oslo Triennale; Le Lieu Unique, Nantes; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Sheffield DocFest. He has lectured and taught at Leeds School of Art, HEAD Geneva, Ensad Paris, HKB Bern, St Lukas Antwerp.

¹: See https://foodculturedays.com/en/program/2023/frca/ ²: Curated by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, the project Critical Zones sought to use the ZKM as an “observatory of […] the new forms of citizenship and new types of attention and care for life forms required to generate a common ground” (Latour & Weibel, 2020), emphasizing how the Earth has entered human politics. It included a seminar, an exhibition, a catalogue, and an abundant program of events between 2019 and 2021.

³: UNESCO Deutschland. (2021). Streuobstanbau. Retrieved from https://www.unesco.de/staette/streuobstanbau/

⁴: Hammel, K., & Arnold, T. (2012). Understanding the loss of traditional agricultural systems: A case study of orchard meadows in Germany. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 2(4), 119-136.

⁵: Mundinger, B. (2022). Paradiese aus zweiter Hand: bedrohte Streuobstwiesen im Ried. Geroldsecker Land, 64, 109-129.

⁶: See https://streuobstinitiative.de

⁷: Bennett, T. (1988). The Exhibitionary Complex. New Formations, No. 4, Spring.

⁸: Rubio, F. D. (2020). Still life: Ecologies of the modern imagination at the art museum. University of Chicago Press.

⁹: About natureculture, see Haraway, D. J. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge. About meshwork, see Ingold, T. (2015). The life of lines. Routledge.

¹⁰: Bishop, C. (2013). Radical museology, or, what's contemporary in museums of contemporary art? Koenig Books.

Bee Boarding School

The Bee Boarding School gathered bees, artists, neighbours, and mediators to converse about art, ecology, alternative economies, and multispecies forms of education. It took place throughout September 2024 on the Katzenwedelwiese, in the form of an exchange between four practitioners from Karlsruhe and four practitioners from the Jatiwangi Arts Factory community in Majalengka, Indonesia. Working as tandems and inhabiting the orchard over the period of the programme, the participating artists and art educators imagined a series of interventions on the orchard as part of the Media Art is Here festival and the ZKM exhibition Fellow Travellers. The neighbours and local communities joined many artistic and culinary events such as a Gado-Gado brunch, a Rajah Lebah honey tea ceremony, a performative walk, and a sunset sound performance, a clay play and beeswax calligraphy workshop, apple and honey tastings, as well as haiku poetry workshop that engaged all the senses. These activities all contributed to expand definitions and boundaries of media art and technology in the middle of a symbiotic living ecosystem.

The experimental curriculum of the Bee Boarding School explored the intersection of media art, ecosystems, education and permacircular economies. In addition to connecting two ecosystems – the Katzenwedelwiese orchard and beehives and the Lemahsugih bee farm collectively managed by the participants from Majalengka – the project sought to raise awareness of biotopes that rely on community care, and connect different groups and local associations. The participating artists and project partners all share a relation to bees and ecological contexts, as well as a curiosity into how media-artistic engagement with alternative educational and economic models can contribute to sustainable futures.

With Aldizar Ahmad Ghifari, Arie Syarifuddin, Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa, Edi Hidayat, Elgea Balzarie, Hanna Jurisch, Lukas Marstaller, Mira Hirtz, Oliver-Selim Boualam, Sayaka Shinkai, Stéphane V. Bottéro, and Yussan Ahmad Fauzi, in kinship with the local citizens’ associations of Bulach and Beiertheim, kindly supported by UNESCO City of Media Arts Karlsruhe, ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, and Sites of Practice.

Recording of sound performance on the Katzenwedelwiese by Yussan Ahmad Fauzi and Lukas Marstaller. 2024.

Post-conversation between Arie Syarifuddin, Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa, Stéphane V. Bottéro (project curators)

SVB: I thought about two questions that we could try to discuss: what was successful with Bee Boarding School? And what could we share with other organisations, or what is something that could feel inspiring to them?

AS: For me, it is the potential to re-think the concept of residency. In Indonesia, we have this kind of thing, like a boarding school, but very short, maybe one week, two weeks. Students are learning from one another, living together, making and experimenting. So taking this collective sharing work and connecting it with the surroundings as well resulted in a really good method.

BZK: Sharing time and sharing practices was really beautiful.

But one thing that was super important was this local rooting within an ecosystem or a biotope, let's say, and really situating the encounter within a very specific place in the critical zone. And in addition to the Katzenwedelwiese we also had the connection to a second ecosystem, which is Lemahsugih. This connection was symbolised by the bees.

SVB: It’s this idea of expanding the school to more than humans. The bees are also students and teachers. And of course the trees, the meadow, and everything in between because they move from flower to tree, from pollen to fruit.

But I think that because an ecosystem like that is so complex, in order to connect and feel empathy, we have to enter from somewhere. We have to step into the critical zone through somewhere. You know, we cannot just pick it up. We know, theoretically, that it's a whole and it's all interconnected. But we are inside it and so at the level of affect and of the stories that we tell, there has to be a place to start, right? So I thought that the bee was a great ambassador of the critical zone.

Now, how can we circulate, like the bees, the knowledge and the methodology with others. Have you thought about this?

AS: We can first try by making a version in Indonesia, then somewhere else. We are already experimenting with this method and then trying to formulate a platform with that very fluid curriculum that we created together. We now have this archive that we can share, as in the lumbung practice (since we have a similar methodology); but I don’t know if scaling up is really effective as the work was about small – but intense – gestures, intimacy, and being very close.

BZK: To me, the chapter that still feels open is to bring the curriculum to Lemahsugih, as it’s about a bridge between to situated contexts that we are building.

It is important to go back, or maybe rather to give back. To fulfil the connection. So to me this feels like a lesson that is still open before being able to bring it to another context.

SB: it’s really good to return to the idea of Lumbung, which is not at all that complete deterritorialization by which everything can travel everywhere and anywhere. Even though the ownership is decentralised, there is some kind of centre in the practice and I think that it’s very important to acknowledge that things start from somewhere and only then they can grow towards elsewhere. It's important to return, but it’s not a return to the same. It's always growth and mutation.

BZK: With the mode of exchange and encounter of Bee Boarding School, it’s something we practice as well, sharing our time, sharing our energy, our curiosity, our knowledge, our practice, our recipes. The idea of Lumbung is a sharing of resources to make something collective from which each one can build something.

This is definitely a method that works in Bee Boarding School, but in combination with a very specific mode of encounter that is situatedness within a very specific biophilic context inside the critical zone. And I think that's maybe what makes the idea of Bee Boarding School really special.

Arie Syarifuddin

Arie Syarifuddin is also known as Alghorie. He is an artist, curator, cultural producer, designer, and director of the artist in residency department of Jatiwangi Art Factory in the village of Jatiwangi in West Java, which is Indonesia’s biggest roof-tile manufacturing center. Redesigning; hacking; giving values and dignity to the ordinary things; negotiation between fiction, dreams, reality, everyday life; and the intersection of historical readings is the most inclination of Arie’s works.

Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa

Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa is a researcher, art mediator, and curator with a passion for community based practices between art, media, and ecology. Apart from her freelance projects, she has worked as a Curator of Education at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Germany, as well as Digital Coordinator at documenta fifteen. She currently researches art education practices in relation to media arts in Korea, Japan, and Indonesia. Together with Fanny Kranz, she has been developing the community of practice called “Mediating Media Arts”, connecting artists, art educators and curators across Japan, Korea, Indonesia, Germany and the Netherlands.

Bee Boarding School

The Bee Boarding School gathered bees, artists, neighbours, and mediators to converse about art, ecology, alternative economies, and multispecies forms of education. It took place throughout September 2024 on the Katzenwedelwiese, in the form of an exchange between four practitioners from Karlsruhe and four practitioners from the Jatiwangi Arts Factory community in Majalengka, Indonesia. Working as tandems and inhabiting the orchard over the period of the programme, the participating artists and art educators imagined a series of interventions on the orchard as part of the Media Art is Here festival and the ZKM exhibition Fellow Travellers. The neighbours and local communities joined many artistic and culinary events such as a Gado-Gado brunch, a Rajah Lebah honey tea ceremony, a performative walk, and a sunset sound performance, a clay play and beeswax calligraphy workshop, apple and honey tastings, as well as haiku poetry workshop that engaged all the senses. These activities all contributed to expand definitions and boundaries of media art and technology in the middle of a symbiotic living ecosystem.

The experimental curriculum of the Bee Boarding School explored the intersection of media art, ecosystems, education and permacircular economies. In addition to connecting two ecosystems – the Katzenwedelwiese orchard and beehives and the Lemahsugih bee farm collectively managed by the participants from Majalengka – the project sought to raise awareness of biotopes that rely on community care, and connect different groups and local associations. The participating artists and project partners all share a relation to bees and ecological contexts, as well as a curiosity into how media-artistic engagement with alternative educational and economic models can contribute to sustainable futures.

With Aldizar Ahmad Ghifari, Arie Syarifuddin, Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa, Edi Hidayat, Elgea Balzarie, Hanna Jurisch, Lukas Marstaller, Mira Hirtz, Oliver-Selim Boualam, Sayaka Shinkai, Stéphane V. Bottéro, and Yussan Ahmad Fauzi, in kinship with the local citizens’ associations of Bulach and Beiertheim, kindly supported by UNESCO City of Media Arts Karlsruhe, ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, and Sites of Practice.

Recording of sound performance on the Katzenwedelwiese by Yussan Ahmad Fauzi and Lukas Marstaller. 2024.

Post-conversation between Arie Syarifuddin, Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa, Stéphane V. Bottéro (project curators)

SVB: I thought about two questions that we could try to discuss: what was successful with Bee Boarding School? And what could we share with other organisations, or what is something that could feel inspiring to them?

AS: For me, it is the potential to re-think the concept of residency. In Indonesia, we have this kind of thing, like a boarding school, but very short, maybe one week, two weeks. Students are learning from one another, living together, making and experimenting. So taking this collective sharing work and connecting it with the surroundings as well resulted in a really good method.

BZK: Sharing time and sharing practices was really beautiful.

But one thing that was super important was this local rooting within an ecosystem or a biotope, let's say, and really situating the encounter within a very specific place in the critical zone. And in addition to the Katzenwedelwiese we also had the connection to a second ecosystem, which is Lemahsugih. This connection was symbolised by the bees.

SVB: It’s this idea of expanding the school to more than humans. The bees are also students and teachers. And of course the trees, the meadow, and everything in between because they move from flower to tree, from pollen to fruit.

But I think that because an ecosystem like that is so complex, in order to connect and feel empathy, we have to enter from somewhere. We have to step into the critical zone through somewhere. You know, we cannot just pick it up. We know, theoretically, that it's a whole and it's all interconnected. But we are inside it and so at the level of affect and of the stories that we tell, there has to be a place to start, right? So I thought that the bee was a great ambassador of the critical zone.

Now, how can we circulate, like the bees, the knowledge and the methodology with others. Have you thought about this?

AS: We can first try by making a version in Indonesia, then somewhere else. We are already experimenting with this method and then trying to formulate a platform with that very fluid curriculum that we created together. We now have this archive that we can share, as in the lumbung practice (since we have a similar methodology); but I don’t know if scaling up is really effective as the work was about small – but intense – gestures, intimacy, and being very close.

BZK: To me, the chapter that still feels open is to bring the curriculum to Lemahsugih, as it’s about a bridge between to situated contexts that we are building.

It is important to go back, or maybe rather to give back. To fulfil the connection. So to me this feels like a lesson that is still open before being able to bring it to another context.

SB: it’s really good to return to the idea of Lumbung, which is not at all that complete deterritorialization by which everything can travel everywhere and anywhere. Even though the ownership is decentralised, there is some kind of centre in the practice and I think that it’s very important to acknowledge that things start from somewhere and only then they can grow towards elsewhere. It's important to return, but it’s not a return to the same. It's always growth and mutation.

BZK: With the mode of exchange and encounter of Bee Boarding School, it’s something we practice as well, sharing our time, sharing our energy, our curiosity, our knowledge, our practice, our recipes. The idea of Lumbung is a sharing of resources to make something collective from which each one can build something.

This is definitely a method that works in Bee Boarding School, but in combination with a very specific mode of encounter that is situatedness within a very specific biophilic context inside the critical zone. And I think that's maybe what makes the idea of Bee Boarding School really special.

Arie Syarifuddin

Arie Syarifuddin is also known as Alghorie. He is an artist, curator, cultural producer, designer, and director of the artist in residency department of Jatiwangi Art Factory in the village of Jatiwangi in West Java, which is Indonesia’s biggest roof-tile manufacturing center. Redesigning; hacking; giving values and dignity to the ordinary things; negotiation between fiction, dreams, reality, everyday life; and the intersection of historical readings is the most inclination of Arie’s works.

Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa

Barbara Zoé Kiolbassa is a researcher, art mediator, and curator with a passion for community based practices between art, media, and ecology. Apart from her freelance projects, she has worked as a Curator of Education at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Germany, as well as Digital Coordinator at documenta fifteen. She currently researches art education practices in relation to media arts in Korea, Japan, and Indonesia. Together with Fanny Kranz, she has been developing the community of practice called “Mediating Media Arts”, connecting artists, art educators and curators across Japan, Korea, Indonesia, Germany and the Netherlands.

Recipe for Sambel Appel

Recipe for Sambel Appel (1 h) Ingredients:

2 Apples 1 Onion 4 tbsp Sunflower Oil 7 Chillis 5 cloves Garlic ½ tbsp Salt

(A) Chop the apples, onion, chilli and garlic very fine

(B) Heat up the sunflower oil very hot

(C) Heat up the onion in the pot with hot oil until slowly golden

(D) Add the apples to the pot and cook until it comes together

(E) Put the chillis and garlic in a different pot with hot oil for 30 sec and then mix it into the other pot

(F) Let it cook for about 30-40 min on low heat

(G) Eat and share it with friends

Recipe for Sighing (5 min)

Ingredients: 1 bit of Space 2 sqm of Floor 1 Body 5 min Time 1-2 Lungs Breath, Vocal Cords, Bones

Environment, Air

(A) Choose a comfortable space and lay down

(B) Close your eyes if comfortable

(C) Let your weight settle into the floor

(D) Notice your breathing:

not like it should be,

but how it is

(E) Notice it’s rhythm and movement

(F) Then on an outbreath, sigh

(G) Do this a few times.

The sigh might change

volume or pitch

Recipe for Gado Gado (12 h)

3 tbsp Peanut Butter

3 Chilli

1 clove Garlic

½ tbsp Soy Sauce

6-9 tbsp Water

Cabbage, Cucumber, Bean Sprouts

add: Eggplants, Green Beans, etc

For the S-a-u-c-e

(A) Smash chili and garlic in a mortar

(B) Mix peanut butter, water and soy sauce in a small bowl until you get a creamy consitency

(C) Add chili and garlic, mix well

For the S-a-l-a-d

(D) Chop the vegetable in thin pieces, mix them in a big bowl

(E) Add the sauce, mix well

(F) Eat and share it with friends

Recipe for Apple Preserve (12 h)

2 Kg freshly harvested apples

2 cinammon sticks

1 pinch salt

sugar to taste if long-term canning

(A) Roughly slice each apple in 4, removing the bad bits but keeping the cores and skin which give a lot of flavor during the cooking. (B) Cook for 1 hour with 2 cups water (to avoid burning the bottom of the pot). (C) Press the cooked apples through a thin sieve. (D) Cook the puree on very low fire for 12 hours, stirring frequently to ensure the caramelized sugars from the fruit don’t stick. Don’t cover so the mixture can evaporate. (E) The apple “butter” should be brown to dark brown if you’ve added sugar, with a smooth thick texture. (F) It can also be done quicker in 1-2 hours on medium fire by stirring constantly.

Recipe for Listening (10 min)

1 bit of Space

2 sqm of Floor

2-4 Bodies

10 min Time

4-8 Ears

Breath, Skin

Bones, Soundwaves

Environment, Air (A) Choose a comfortable space and sit down

(B) Lean your backs against each other

(C) Close your eyes if comfortable

(D) Let your weight sink backwards

(E) Take time and breath

(F) Listen to the sounds:

a. close and far, outside your bodies

b. close and far, inside your bodies

(G) Open your eyes and share what you heard while still sitting

Recipes shared by Bee Boarding School Collective. BBS © All bites preserved, 2024

Recipe for Sambel Appel

Recipe for Sambel Appel (1 h) Ingredients:

2 Apples 1 Onion 4 tbsp Sunflower Oil 7 Chillis 5 cloves Garlic ½ tbsp Salt

(A) Chop the apples, onion, chilli and garlic very fine

(B) Heat up the sunflower oil very hot

(C) Heat up the onion in the pot with hot oil until slowly golden

(D) Add the apples to the pot and cook until it comes together

(E) Put the chillis and garlic in a different pot with hot oil for 30 sec and then mix it into the other pot

(F) Let it cook for about 30-40 min on low heat

(G) Eat and share it with friends

Recipe for Sighing (5 min)

Ingredients: 1 bit of Space 2 sqm of Floor 1 Body 5 min Time 1-2 Lungs Breath, Vocal Cords, Bones

Environment, Air

(A) Choose a comfortable space and lay down

(B) Close your eyes if comfortable

(C) Let your weight settle into the floor

(D) Notice your breathing:

not like it should be,

but how it is

(E) Notice it’s rhythm and movement

(F) Then on an outbreath, sigh

(G) Do this a few times.

The sigh might change

volume or pitch

Recipe for Gado Gado (12 h)

3 tbsp Peanut Butter

3 Chilli

1 clove Garlic

½ tbsp Soy Sauce

6-9 tbsp Water

Cabbage, Cucumber, Bean Sprouts

add: Eggplants, Green Beans, etc

For the S-a-u-c-e

(A) Smash chili and garlic in a mortar

(B) Mix peanut butter, water and soy sauce in a small bowl until you get a creamy consitency

(C) Add chili and garlic, mix well

For the S-a-l-a-d

(D) Chop the vegetable in thin pieces, mix them in a big bowl

(E) Add the sauce, mix well

(F) Eat and share it with friends

Recipe for Apple Preserve (12 h)

2 Kg freshly harvested apples

2 cinammon sticks

1 pinch salt

sugar to taste if long-term canning

(A) Roughly slice each apple in 4, removing the bad bits but keeping the cores and skin which give a lot of flavor during the cooking. (B) Cook for 1 hour with 2 cups water (to avoid burning the bottom of the pot). (C) Press the cooked apples through a thin sieve. (D) Cook the puree on very low fire for 12 hours, stirring frequently to ensure the caramelized sugars from the fruit don’t stick. Don’t cover so the mixture can evaporate. (E) The apple “butter” should be brown to dark brown if you’ve added sugar, with a smooth thick texture. (F) It can also be done quicker in 1-2 hours on medium fire by stirring constantly.

Recipe for Listening (10 min)

1 bit of Space

2 sqm of Floor

2-4 Bodies

10 min Time

4-8 Ears

Breath, Skin

Bones, Soundwaves

Environment, Air (A) Choose a comfortable space and sit down

(B) Lean your backs against each other

(C) Close your eyes if comfortable

(D) Let your weight sink backwards

(E) Take time and breath

(F) Listen to the sounds:

a. close and far, outside your bodies

b. close and far, inside your bodies

(G) Open your eyes and share what you heard while still sitting

Recipes shared by Bee Boarding School Collective. BBS © All bites preserved, 2024

The Cycle of Cosmic Fruitness

The Cycle of Cosmic Fruitness is a performance that took place on the Katzenwedelwiese in March 2022. It invited the local community and orchard caretakers to a series of warm-up exercises to prepare the body for pruning and maintenance activities. Borrowing from astrology, biodynamics, somatics and holistic healing practices, this playful, participative activity proposed a secret initiation to fruit astrology and mystic gardening. The fruitness fan (ink on thai paper) offers guidance on the transformation pathway.

Based on the performance script and his own impressions of the orchard, London-based musician Oliver Say created an immersive sound piece. In this process, Say imagined himself as one of the many beings inhabiting the meadow, composing the piece using only his own voice which he sampled into a virtual synthetiser. Playing with frequency stretches and tonal improvisation, the vocalization is analogous to the singing of insects or birds.

The Cycle of Cosmic Fruitness

The Cycle of Cosmic Fruitness is a performance that took place on the Katzenwedelwiese in March 2022. It invited the local community and orchard caretakers to a series of warm-up exercises to prepare the body for pruning and maintenance activities. Borrowing from astrology, biodynamics, somatics and holistic healing practices, this playful, participative activity proposed a secret initiation to fruit astrology and mystic gardening. The fruitness fan (ink on thai paper) offers guidance on the transformation pathway.

Based on the performance script and his own impressions of the orchard, London-based musician Oliver Say created an immersive sound piece. In this process, Say imagined himself as one of the many beings inhabiting the meadow, composing the piece using only his own voice which he sampled into a virtual synthetiser. Playing with frequency stretches and tonal improvisation, the vocalization is analogous to the singing of insects or birds.