The Art of Living on the Rift

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino, Teesa Bahana, Margaux Schwab

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino, Teesa Bahana, Margaux Schwab

Margaux Schwab (foodculture days): Precisely three years ago, foodculture days embarked on a new online editorial chapter by launching Boca A Boca. The intention was to deepen our understanding around certain themes that we question and that question us in return. Each invited guest editor brings their situated perspective, network and sensibilities, allowing the transdisciplinary perspective so dear to us to emerge organically. The intention is to question the role of art and artists in supporting social and political movements of change on multiple scales and, simultaneously, providing them with a platform to expose our western gaze and its implications.

For this new editorial season, beyond enriching the public’s perspective on what African art is, what is primarily at stake is the meaning of its values and the potential of their expression in everyday life.

Catherine Lie, Sourdough Architecture (detail), 2024, KLA ART Festival, Ganzu Lumumba Ave. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

KLA ART festival (by 32° East, an art and residency center founded in 2011 in Kampala) and foodculture days Biennale share many approaches to field-research, slower cultural work and festival-making, as well as audience/community reach. Together with its director, Teesa Bahana, we realized that we shared a common aspiration: to better understand the most important conditions for enabling sustainable artistic processes rooted in the territory as well as a common longing for growing otherwise.

For its 5th edition, KLA ART festival focused on cultural heritage through the lens of care instructions for the living world. A reflection echoing with foodculture days’ vision on the multiple ways a festival can be(come) a platform to encourage different communities to explore multiple relationships with its surroundings. Together, we celebrate cooking and food as one of the few media that express complex ecologies and territories so well. By letting what is outside enter your body, each bite becomes a manifestation of the interdependence of matter and affects. Eating makes us vulnerable.

By envisioning a nonlocal approach, this cycle inquires how we might try to mitigate the colonial violence inherent in fixed identities and so called cultural differences by letting the mouth be “a portal, an entrance, a door”, as Lucy Cordes Engelman wrote it already in her contribution to an early cycle of Boca A Boca back in 2023. Once again, I am delighted to see how Boca A Boca has turned into a potent tool to get to know new people, e.g., 32° EAST and KLA ART festival teams, or deepen existing relations, like with Mateo Chacón Pino, and connect with our publics through an infinite composition of contributions where every entity is an expression of all others.

32° East/KLA ART: Taking inspiration from the traditional ritual of inter-generational fireside conversations present in many Ugandan cultures, 32° East’s Ekyooto sessions are aimed at facilitating open and non-hierarchical discussions that bring diverse generations together to participate in this longheld alternative knowledge system.

Preparations for Ekyooto, 2024, KLA ART Festival, field behind 32° East. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

Our inaugural Ekyooto took place during KLA ART ‘24, led by Kassel-based art historian and curator Mateo Chacón Pino. These conversations explored the intersection of art, ecology, care, and curatorship within both local and global contexts. The sessions which highlighted the need for alternative knowledge-sharing platforms attracted large audiences, and overwhelmingly positive feedback from attendees and 32° East members. Responding to this need, we made Ekyooto a regular part of our 2025 programming, hosting four sessions featuring diverse themes aimed at fostering knowledge exchange, skill sharing, and open discussions on contemporary art and its role in society.

Ekyooto, 2024, KLA ART Festival, field behind 32° East. Photo: 32° East

Mateo Chacón Pino: When preparing for my research trip to Kampala, Uganda, I intended to look for similarities between the artists at KLA ART Festival and the contributors at foodculture days’ Biennale. I was playing the old European train of thought of placing similar things or thoughts together, separating what is different–a base for Linnean thought on species or Cartesian space. Little did I expect to encounter a reality that did not meet my imagination; an embodiment of difference without separability, a thought developed by Brazilian thinker Denise Ferreira da Silva, through food. Personally, I am used to visiting German and Swiss markets and seeing a large variety of apples, each with their distinct taste, e.g., sweet, aromatic, fresh, sour, size or color. Some apples offer themselves for distinct uses depending on their qualities; baking, juice, as snacks, or even as jams. We know the seasons and the regions–variety and diversity are not an expression of politics but rather of culture/agriculture. Yet its kitchentable cousin, the banana, experiences barely a fragment of the same recognition: the European palate only ever tastes the humble Cavendish banana, the dominant global variety as an outcome between ecological resistance through infections and capital-driven monoculture. Whereas East African culture is intimately familiar with a large variety of bananas. As Rebecca Khamala writes you might not find a banana in Uganda, but matooke, embidde, bogoya, and more, all with their own qualities and uses. And often I would hear from those I met which variety they prefer, with little difference to a conversation with Swiss friends about which apple variety they enjoy the most. Rather, the differences highlight the human inability to escape ecological dependencies, despite modernity, capitalism and, most importantly, the attempt to replace ecology through technological means.

Brogan Mwesigwa, Kumanyagana (detail), 2024, KLA ART Festival, Ganzu Lumumba Ave. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

What these attempts do, in erasing differences that make us human and alienating us from each others humanity, is discussed through Jim Chuchu’s film contribution; an essay in giving an appropriate image to the human-made famine in Eastern Africa without falling into the pitfalls of reproducing poverty porn and exoticism. Similarly, Cassiane Pfund opens a poetic debate whether it is new images, new words that are needed or, in my reading, whether we should rather organize quickly. The conversation between Brogan Mwesigwa and Sandra Knecht bridges across multiple differences simultaneously: between Switzerland and Uganda–the Global North and the Global South–, between different generations of artists, and between gendered experiences of living and working within an ecology.

As much as we may share the fact that our lives are being shaped by climate catastrophe, the differences between us and others really only reflect on our own social, economic, political and ecological position. Whether someone suffers more or less does not change our own experience, yet it may help teach us which strategies may or may not be suitable for our individual situation.

This cycle’s title is a reference to Marxian metabolic rift, the disconnect between capitalist logic and natural resources which leads to ecological crises, as is the current climate catastrophe. No matter where we live and under which circumstances; no one will evade the consequences of extractive and monocultural agroeconomy, with the implication that human survival hinges on collaboration and action rather than on techno-solutions or human-centric politics. And this is perhaps what the arts of living on the rift may be: an attempt to acknowledge the distinct experience of being a political agent and subject to ecology, no matter where we live, and attempt to thrive in solidarity. These arts are realist in the sense that it deals with material reality instead of articulating speculation. It is not an exercise in awareness, after all, the torturer is most aware of the victim’s pain. Instead, it is a moral stance for the ecological dimension of any cultural practice, a learning through horizontal difference.

Mateo Chacón Pino (CO/CH) is a an art historian, curator and author. He has curated projects in art spaces, museums, galleries and farms in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany. He participated in The Curatorial and Artistic Thing at the sixtyeight art institute in Copenhagen and the Curatorial Program at De Appel, Amsterdam.

Mateo Chacón Pino currently lives in Kassel and works as a research assistant at the documenta Institute and at the University of Kassel in the Department of Art and Society, under Prof. Dr. Liliana Gómez.

In his dissertation "The Distinction of Art & Nature" he questions the epistemic time of art history in the light of the Anthropocene and problematizes the concept of contemporary art in the context of the exhibition. He completed his master's thesis in 2021 at the University of Zurich under Prof. Dr. Bärbel Küster on the role of state art funding for the understanding of art using the case study of the SüdKulturFonds in Switzerland. Further research interests include the social and epistemological conditions of art, the history of knowledge and philosophy of art history, as well as the problem area of aesthetics and sustainability. His work is motivated by the question of the role of art in the transformation to a sustainable society.

Together with Friederike Schäfer he is co-initiator of the research group "Exhibition Ecologies" and he is a member of the Creative Climate Leadership Switzerland network, which is led by Julie's Bicycle.

Teesa Bahana (UGA) is director of 32° East, a not-for-profit that promotes the creation and exploration of contemporary art in Uganda. As director she has supported the development and execution of projects such as KLA ART Labs for research and critical thinking through public practice, KLA ART, Kampala's public art festival, and residency exchanges with partners such as Arts Collaboratory, and Triangle Network.

She is also currently overseeing 32° East's capital project, raising funds to build the first purpose-built art centre in Kampala. With an academic background in sociology and anthropology, she is particularly interested in the intersection between art and Ugandan society, and how artistic environments should be protected and nurtured.

Before her directorship at 32° East, she was on the inaugural organisation committee for Nyege Nyege International Music Festival, and worked in communications and external relations for educational non-profits in Rwanda, Burundi and South Africa. She has spent the last year on study leave getting an MA in Anthropology of Global Futures and Sustainability at SOAS University of London.

Margaux Schwab (CH/MX) lives and works in Vevey after spending ten years in Berlin. She is a cultural producer, researcher, and curator working with the ecologies and politics of the living through food and its imaginaries.

In 2015, she founded foodculture days in Vevey, Switzerland, a platform for sharing knowledge and practices that hosts research, pedagogical, and editorial projects online. The outcome of these continuous exchanges is the foodculture days Biennial, which takes place every two years, free of charge, in the public spaces of Vevey. By valuing kitchens, markets, fields, orchards, and gardens as powerful spaces for the transmission of knowledge and know-how, Schwab is interested in the role of art(ists) in transforming food systems and in how they can connect us to our foodscapes in sensitive, sensorial, and engaged ways.

Since 2025, she is a guest lecturer at the University of Art and Design Basel, Switzerland, within the Co-Create program.

The Art of Living on the Rift

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino, Teesa Bahana, Margaux Schwab

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino, Teesa Bahana, Margaux Schwab

Margaux Schwab (foodculture days): Precisely three years ago, foodculture days embarked on a new online editorial chapter by launching Boca A Boca. The intention was to deepen our understanding around certain themes that we question and that question us in return. Each invited guest editor brings their situated perspective, network and sensibilities, allowing the transdisciplinary perspective so dear to us to emerge organically. The intention is to question the role of art and artists in supporting social and political movements of change on multiple scales and, simultaneously, providing them with a platform to expose our western gaze and its implications.

For this new editorial season, beyond enriching the public’s perspective on what African art is, what is primarily at stake is the meaning of its values and the potential of their expression in everyday life.

Catherine Lie, Sourdough Architecture (detail), 2024, KLA ART Festival, Ganzu Lumumba Ave. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

KLA ART festival (by 32° East, an art and residency center founded in 2011 in Kampala) and foodculture days Biennale share many approaches to field-research, slower cultural work and festival-making, as well as audience/community reach. Together with its director, Teesa Bahana, we realized that we shared a common aspiration: to better understand the most important conditions for enabling sustainable artistic processes rooted in the territory as well as a common longing for growing otherwise.

For its 5th edition, KLA ART festival focused on cultural heritage through the lens of care instructions for the living world. A reflection echoing with foodculture days’ vision on the multiple ways a festival can be(come) a platform to encourage different communities to explore multiple relationships with its surroundings. Together, we celebrate cooking and food as one of the few media that express complex ecologies and territories so well. By letting what is outside enter your body, each bite becomes a manifestation of the interdependence of matter and affects. Eating makes us vulnerable.

By envisioning a nonlocal approach, this cycle inquires how we might try to mitigate the colonial violence inherent in fixed identities and so called cultural differences by letting the mouth be “a portal, an entrance, a door”, as Lucy Cordes Engelman wrote it already in her contribution to an early cycle of Boca A Boca back in 2023. Once again, I am delighted to see how Boca A Boca has turned into a potent tool to get to know new people, e.g., 32° EAST and KLA ART festival teams, or deepen existing relations, like with Mateo Chacón Pino, and connect with our publics through an infinite composition of contributions where every entity is an expression of all others.

32° East/KLA ART: Taking inspiration from the traditional ritual of inter-generational fireside conversations present in many Ugandan cultures, 32° East’s Ekyooto sessions are aimed at facilitating open and non-hierarchical discussions that bring diverse generations together to participate in this longheld alternative knowledge system.

Preparations for Ekyooto, 2024, KLA ART Festival, field behind 32° East. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

Our inaugural Ekyooto took place during KLA ART ‘24, led by Kassel-based art historian and curator Mateo Chacón Pino. These conversations explored the intersection of art, ecology, care, and curatorship within both local and global contexts. The sessions which highlighted the need for alternative knowledge-sharing platforms attracted large audiences, and overwhelmingly positive feedback from attendees and 32° East members. Responding to this need, we made Ekyooto a regular part of our 2025 programming, hosting four sessions featuring diverse themes aimed at fostering knowledge exchange, skill sharing, and open discussions on contemporary art and its role in society.

Ekyooto, 2024, KLA ART Festival, field behind 32° East. Photo: 32° East

Mateo Chacón Pino: When preparing for my research trip to Kampala, Uganda, I intended to look for similarities between the artists at KLA ART Festival and the contributors at foodculture days’ Biennale. I was playing the old European train of thought of placing similar things or thoughts together, separating what is different–a base for Linnean thought on species or Cartesian space. Little did I expect to encounter a reality that did not meet my imagination; an embodiment of difference without separability, a thought developed by Brazilian thinker Denise Ferreira da Silva, through food. Personally, I am used to visiting German and Swiss markets and seeing a large variety of apples, each with their distinct taste, e.g., sweet, aromatic, fresh, sour, size or color. Some apples offer themselves for distinct uses depending on their qualities; baking, juice, as snacks, or even as jams. We know the seasons and the regions–variety and diversity are not an expression of politics but rather of culture/agriculture. Yet its kitchentable cousin, the banana, experiences barely a fragment of the same recognition: the European palate only ever tastes the humble Cavendish banana, the dominant global variety as an outcome between ecological resistance through infections and capital-driven monoculture. Whereas East African culture is intimately familiar with a large variety of bananas. As Rebecca Khamala writes you might not find a banana in Uganda, but matooke, embidde, bogoya, and more, all with their own qualities and uses. And often I would hear from those I met which variety they prefer, with little difference to a conversation with Swiss friends about which apple variety they enjoy the most. Rather, the differences highlight the human inability to escape ecological dependencies, despite modernity, capitalism and, most importantly, the attempt to replace ecology through technological means.

Brogan Mwesigwa, Kumanyagana (detail), 2024, KLA ART Festival, Ganzu Lumumba Ave. Photo: Mateo Chacón Pino

What these attempts do, in erasing differences that make us human and alienating us from each others humanity, is discussed through Jim Chuchu’s film contribution; an essay in giving an appropriate image to the human-made famine in Eastern Africa without falling into the pitfalls of reproducing poverty porn and exoticism. Similarly, Cassiane Pfund opens a poetic debate whether it is new images, new words that are needed or, in my reading, whether we should rather organize quickly. The conversation between Brogan Mwesigwa and Sandra Knecht bridges across multiple differences simultaneously: between Switzerland and Uganda–the Global North and the Global South–, between different generations of artists, and between gendered experiences of living and working within an ecology.

As much as we may share the fact that our lives are being shaped by climate catastrophe, the differences between us and others really only reflect on our own social, economic, political and ecological position. Whether someone suffers more or less does not change our own experience, yet it may help teach us which strategies may or may not be suitable for our individual situation.

This cycle’s title is a reference to Marxian metabolic rift, the disconnect between capitalist logic and natural resources which leads to ecological crises, as is the current climate catastrophe. No matter where we live and under which circumstances; no one will evade the consequences of extractive and monocultural agroeconomy, with the implication that human survival hinges on collaboration and action rather than on techno-solutions or human-centric politics. And this is perhaps what the arts of living on the rift may be: an attempt to acknowledge the distinct experience of being a political agent and subject to ecology, no matter where we live, and attempt to thrive in solidarity. These arts are realist in the sense that it deals with material reality instead of articulating speculation. It is not an exercise in awareness, after all, the torturer is most aware of the victim’s pain. Instead, it is a moral stance for the ecological dimension of any cultural practice, a learning through horizontal difference.

Mateo Chacón Pino (CO/CH) is a an art historian, curator and author. He has curated projects in art spaces, museums, galleries and farms in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany. He participated in The Curatorial and Artistic Thing at the sixtyeight art institute in Copenhagen and the Curatorial Program at De Appel, Amsterdam.

Mateo Chacón Pino currently lives in Kassel and works as a research assistant at the documenta Institute and at the University of Kassel in the Department of Art and Society, under Prof. Dr. Liliana Gómez.

In his dissertation "The Distinction of Art & Nature" he questions the epistemic time of art history in the light of the Anthropocene and problematizes the concept of contemporary art in the context of the exhibition. He completed his master's thesis in 2021 at the University of Zurich under Prof. Dr. Bärbel Küster on the role of state art funding for the understanding of art using the case study of the SüdKulturFonds in Switzerland. Further research interests include the social and epistemological conditions of art, the history of knowledge and philosophy of art history, as well as the problem area of aesthetics and sustainability. His work is motivated by the question of the role of art in the transformation to a sustainable society.

Together with Friederike Schäfer he is co-initiator of the research group "Exhibition Ecologies" and he is a member of the Creative Climate Leadership Switzerland network, which is led by Julie's Bicycle.

Teesa Bahana (UGA) is director of 32° East, a not-for-profit that promotes the creation and exploration of contemporary art in Uganda. As director she has supported the development and execution of projects such as KLA ART Labs for research and critical thinking through public practice, KLA ART, Kampala's public art festival, and residency exchanges with partners such as Arts Collaboratory, and Triangle Network.

She is also currently overseeing 32° East's capital project, raising funds to build the first purpose-built art centre in Kampala. With an academic background in sociology and anthropology, she is particularly interested in the intersection between art and Ugandan society, and how artistic environments should be protected and nurtured.

Before her directorship at 32° East, she was on the inaugural organisation committee for Nyege Nyege International Music Festival, and worked in communications and external relations for educational non-profits in Rwanda, Burundi and South Africa. She has spent the last year on study leave getting an MA in Anthropology of Global Futures and Sustainability at SOAS University of London.

Margaux Schwab (CH/MX) lives and works in Vevey after spending ten years in Berlin. She is a cultural producer, researcher, and curator working with the ecologies and politics of the living through food and its imaginaries.

In 2015, she founded foodculture days in Vevey, Switzerland, a platform for sharing knowledge and practices that hosts research, pedagogical, and editorial projects online. The outcome of these continuous exchanges is the foodculture days Biennial, which takes place every two years, free of charge, in the public spaces of Vevey. By valuing kitchens, markets, fields, orchards, and gardens as powerful spaces for the transmission of knowledge and know-how, Schwab is interested in the role of art(ists) in transforming food systems and in how they can connect us to our foodscapes in sensitive, sensorial, and engaged ways.

Since 2025, she is a guest lecturer at the University of Art and Design Basel, Switzerland, within the Co-Create program.

WHICH RITUALS FOR THE FUTURE, WHICH RITUALS FOR NOW ? on commemoration and uncertainty – by Cassiane Pfund

to begin with

i wished to imagine rituals for the future

to fill a blank

to defy despair

to make celebrations and find communities

to embrace trust and name hope

an unpleasant truth is that i don’t know anymore

i don’t know where to start

nor how to (dis)continue

I don’t know

and not knowing now feels harder than ever...

but have i ever known anyway?

and you, have you ever known anyway?

what i observe from here, in switzerland, is that a certain

amount of recent art works and exhibitions, texts, research

programs and open calls is directed towards detangling,

unfolding, expanding, hacking, recreating, building, undoing,

reshaping, reinventing and designing future(s)...

but what would be

what would it sound or taste like

a future to yearn for?

00. what tongue(s)?

storytelling and underground stories have probably been an act

of resisting oppressions and uncertainties, an act of imagining

alternative solutions and gathering since human beings can

speak.

when mateo chacón pino contacted me to write a text, my

mouth felt dry as if my tongue was gone, and words were barely

present. i asked myself:

do we need more and more and more and more words?

in an attempt to grasp something from a landscape my fingers

don’t recognize most textures of

from futures that feel blurry

–unimaginable and distant, yet so close–

i sit by the river

searching sediments and pebbles for another tongue

a sensory one for

what is

what resists

what evolves

what survives

a tongue that dances

a tongue that doubts and trusts

a tongue that listens

a tongue for now

pause

gravity is what has the capacity to make bodies sink, just as

much as it allows them to be held, for as long as a ground

remains.

–in any case

we will learn to breathe

we will learn to swim

they say

who is we?

who is they?

pause

for now

close your eyes

your own flesh

merged with water

feels like the translucent one of a jellyfish

marine mammals¹

appear

marine heatwaves the moment after

and the same melody

again and again

reminding you of a sacred foundation

creatures that came before

all those who will hopefully come after

01. future(s)

if tomorrow can be understood as much as

the day after today

a period of time close to now

a few decades centuries ahead

or even when the sun explodes

–and yet probably some time before–

what future(s) are we talking about?

what is meant to be understood when the word ‘future’ is used?

is it really and only a matter of time?

and what would make future(s) possible?

I read somewhere that quantum physics and ongoing

research keep showing us how little our understanding of the

future is. fascinating enough, it feels like time perceived as

linear

tends to mimic a common representation of human life; a

chronological timeline starting with birth and ending with

death.

but is it really?

in the piece niagara 3000, the artist pamina de coulon says

le futur vient de l’amont²

future comes from upstream

pause

for now

I close my eyes

the same melody unfolds

creatures who came before

those who will come after

02. where to start?

a place to start could be causality, whilst keeping in mind the

richness and uncertainty of multifactoriality, that is,

when different factors are involved and it becomes complex to

tell which causes what and how. ie, it can be very difficult to

identify what cause(s) migraines because different elements

are, most of the time, commonly identified to

be(come) potential triggers, such as food, stress, sensory

stimulation, pollution, abuse, etc., and in many cases, they tend

to be combined. this is when a holistic vision tends to

highlight the notions of system and ecosystem.

if part of what a future to yearn for may be like partially depends

on how we, as societies, decide to take action, on what we, as

societies, decide to embody and nurture,

how to prepare the bed for such futures now?

how can we find ways through by embracing the discomfort of

uncertainty?

how can we allow ourselves to grieve, not as a sign of despair,

rather as a way of integrating the fragility of life and

reactivating our love for the earth we live on?

and again, who is we?

in her last book vivre libre³, amandine gay expresses with clarity

how the desire to transform society must be thought of as a

collective effort that starts with an intimate movement. she

writes:

we aspired to transform society without being aware

that it started with our own liberation from norms that

are productivism, competition, need for attention or

even precarity.⁴

her vision offers the chance to both come back to one’s own

situated body through decentering oneself from normativity with

a certain lucidity regarding how falling into the trap of white

supremacy–by both internalizing and reproducing its tools–needs to be talked about, not with the intention of blaming

individuals, but as a reminder of where such transformation

starts with.

03. hierarchised knowledge⁵, and bodies

in 2016, i remember an introductory class on

epistemology⁶ and the exam i wonderfully failed at. i found

myself having difficulties at engaging with the subject as the

approach was lacking something i needed, something crucial i

struggled to identify at the time. i then started to look around to

soon realize that, at the time, the department–in which i tried

to fit in not without anxiety–had a tendency to deeming itself

as a temple of knowledge whilst actually failing at

reporting on diversity of knowledge, as well as broadening

perspectives, representations and points of view.

a year later, i meet marie lefebvre–a researcher based in

montreal who i am happy to call friend– she introduced

me to both a philosophical and social practice which aims to decenter a

commonly shared view on (brain perceived)

intelligence and knowledge. such practice underlines

the necessity of both listening to–in a broad sense–and

considering every person as a potential epistemic agent in the

sense that everyone can be learned from. this vision makes

space for both a redistribution of power, and

questioning stereotypes as well as other hindrances to

legitimacy.

here are two definitions of knowledge from the merriam

webster dictionary⁷:

the circumstance or condition of apprehending truth,

fact, or reality immediately with the mind or senses.

the sum of what is known: the body of truth,

information, and principles acquired by humankind.⁷

i wonder how could coexist different modes of knowledge

acquisition without hierarchies, and beyond these very modes,

how to collectively aim towards what marie explained to me.

and what about access to knowledge?

could it be that the absence of situated bodies within such an

analytic field was a central factor of the

disconnection i experienced?

and if yes, how to value body intelligence and operate from a

common ground: we experience and feel–in our own sensitive

ways–, therefore we belong?

cultivating long term visions contributes to giving a more

consistent direction to actions and helps find meaning.

however, whilst imagining futures is crucial, it cannot be

sufficient as the act of imagining itself is intertwined with the

now⁸, and i will even say, with situated nows.

a future to yearn for won’t magically happen

without taking accountability

without dismantling any kind of supremacy

without feeling

and coming back to (our) bodies with radical honesty

04. epistemic injustice

the notion of epistemic injustice invented by miranda fricker⁹,

invites to address the question of knowledge as power. indeed,

who is perceived as contributing to the creation of knowledge

and who is not? which voices are heared, which are ignored

and which are silenced?

each time a voice is ignored and silenced,

what will be remembered from the past shrinks already, and

with it, an understanding of the present. to feel a sense of the

present(s) that is or are being lived, and project any type of

possible future, there is an essential urge to work towards

resisting separation.

like many authors and artists, wendy

delorme¹⁰ reaffirms in an interview with constant spina for censored magazine¹¹,

reaffirms separation:

nous sommes un tout : humains, arbres, montagnes,

cours d’eau et animaux. tout le monde du vivant est

interconnecté, interdépendant. c’est très simple, c’est

une évidence, et pourtant, de par nos modes de vie

d’aujourd’hui, on ne cesse de l’oublier.¹²

we are one: humans, trees, mountains, rivers

and animals. all living things are

interconnected and interdependent. it's very

simple, it's obvious, and yet, because of our

lifestyles today, we keep forgetting it.

an article on epistemic (knowledge) injustice within the field of

psychiatry research provides an understanding of the concept:

epistemic injustice is a form of systemic discrimination

relating to the creation of knowledge. it occurs when

people from marginalized groups are denied capacity

as ‘epistemic agents’ (i.e., as creators of knowledge),

and are diminished or excluded from the process of

creating meaning. such exclusion creates conditions

in which the lived experiences of marginalized people

are primarily interpreted by people who do not share

their social position.[...] as an approach, lived

experience work recognized that marginalized people

are rarely afforded the opportunity to theorize their own

experiences and generate solutions.¹³

the authors of the article mention and warn against the risk of

epistemic exploitation, which appears to be another form of

extractivism when these lived experiences are absorbed within

existing dominant structures where they become tokens¹⁴. in

reality, the question of the lived experiences, when facing

extractivism mecanisms, is deeply intertwined with colonial

thinking:

[the question of the lived experiences] has

encountered an inherent problem though in seeking

to challenge western traditional valuing of positivist

approaches to research, with their emphasis on

‘objectivity’, ‘neutrality’ and ‘distance’. these are still strong

in the psych system and have distorted our

understandings of what counts as knowledge. so, if you

have direct experience of a problem, like poverty,

distress or indeed colonisation, where such research

values apply, you can expect to be granted less credibility

and your knowledge seen as less reliable

because you are ‘too close to the problem’ – it affects you

and you cannot claim to be neutral, objective and distant

from it. thus, you can expect to be seen as an inferior

knower and your knowledge less reliable. this

means effectively that if you have experience of

discrimination and oppression you can expect

routinely to face further discrimination and be further

marginalised and devalued.¹⁵

05. sensitive knowledge

the centre d’archivage des savoirs sensibles, an art work by the

company création dans la chambre¹⁶ which connects popular

archives, knowledge(s) and memory, moved me deeply. here is

the description i found on their website:

cette installation monumentale d’archivage populaire

offerte aux citoyen-n-e-x-s deviendra en quelque sorte

un lieu d’échange poétique d’apprentissage, sans

discrimination quant à l’autorité d’un savoir sur un

autre; nous voulons proposer un espace déhiérarchisé

où tou-x-t-e-s peuvent laisser quelque chose au monde

dans une optique de transmission. que ce soit par un

enseignement artisanal unique, une chanson cachée

dans un vieux souvenir, l’histoire d’un-e-x aïeul-e-x

transmise par l’oralité, une recette familiale ancestrale

ou l’étude toute personnelle d’un comportement

animalier, chacun pourra agir sur la mémoire collective

en perpétuelle construction.

the centre d’archivage du savoir sensible highlights an

important dimension: knowledge cannot be reduced to one

single type or category. vigilance and humility are required to

avoid establishing competition or hierarchy

between one another, and be aware of where they come from

and/or were taken from.

06. lineage & commemoration

whilst i wonder what the tools to help us embody such

a change of perspective could be, commemorating visits me.

what will remain if there is no one to remember?

some weeks ago, at a round table organized by the association

afrikalab¹⁷, co-moderated by ivan larson ndenguewith germaine

acogny and shelly ohene-nyako, the notion of lineage appeared

as an essential way of both honouring and remembering who

we learned and still learn from.

commemoration is an act of togetherness

one of collective resistance

which prevents memory from being erased

a ritual to keep traces

bring them back to life for a moment

before transmitting them further

i like to see it as a cycle of honoring what came before

receiving

listening

learning

questioning

refusing

nurturing

transforming

then confiding

a cycle having its own rythms which requires

slowness and presence

awareness and proximity

being aware of what made life possible

invites us to proceed to an ongoing choreography

a movement which defies linearity

bringing ancient memories

asking to adjust

to learn

to choose what we keep honoring

what we’ll have transformed

–or tried to–

to be aware of the traces we may leave

and repeat

from where i write

and for now

this ground remains.

cassiane c. pfund (BR/CH)’s practice situates itself in the interstices. reassembling writing, art, research and poetry, it considers words as a starting point from which to explore other media such as performance, installation and publishing as sculptures and collective experiences of transmission. its wish is to open up slow spaces where people can meet, exchange stories, feel their emotions and raise questions.

cassiane c. pfund (*1993) lives in Geneva. first trained as a philosopher (ma degree, unige & uqam, 2018), they then desired to feel and deepen concepts from a body and interdisciplinary artistic perspective. (ma cap, hbk, 2020)

website: cassianepfund.ch

[1] the expression ‘marine mammals’ is borrowed from author and

researcher alexis pauline gumps and her text undrowned: black feminist

lessons learned from marine mammals, ak press (2020).

[2] niagara 3000 is a performance by artist and author pamina de

coulon from the fire of emotions saga.

[3] gay amandine, vivre libre, exister au cœur de la suprématie blanche,

cahiers libres, la découverte, october 2025.

[4] ibid., p.114.

[5] in english, the term ‘knowledge’ refers indiscriminately to both

learning and understanding, which is not the case in french.

[6] the introductory course in epistemology is a compulsory module in

philosophy studies at the university of geneva.

[7] this definition is taken from the meriam webster dictionary:

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/knowledge

[8] during her talk at the w.o.r.d. school, author and activist sarah

durieux introduced the importance of anchoring discourse in the

present when it comes to storytelling and political discourse.

[9] history records that the concept of epidemic injustice was first

formulated by philosopher miranda fricker.

[10] wendy delorme is a french author, performer, teacher, researcher

and feminist activist.

[11] censored magazine is an editorial platform where feminist ideas,

emerging creativity and transmission intersect, beyond the dominant

narratives.

[12] Ibid., constant spina (2025), interview with wendy delorme: le

roman comme un cycle de l’eau, [online].

[13] celestin okoroji, tanya mackay, dan robotham, dation beckford,

Vanessa Pinfold (2023), Epistemic injustice and mental health research:

a pragmatic approach to working with lived experience expertise,

frontiers in psychiatry, vol. 14, [online],

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.

2023.1114725/full

[14] tokenism refers to the practice whereby a group or organisation

includes people from minority backgrounds without making any real

structural changes or providing them with long-term support, as it is in

fact a case of superficial inclusion.

[15] peter beresford, diana rose (2023), decolonising global mental

health: the role of mad studies, cambridge prisms: global mental health,

cambridge university press, [online],

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/global-mental-health/article/

decolonising-global-mental-health-the-role-of-mad-studies/

EEF259FE948CAA0E25E57036D547EBFC.

[16] the centre d'archivage des savoirs sensibles is a project created by

the quebec-based company création dans la chambre:

https://www.creationdanslachambre.com/

[17] afrikalab is a venue dedicated to culture, ‘living together’,

transmission and training in the city of geneva.

WHICH RITUALS FOR THE FUTURE, WHICH RITUALS FOR NOW ? on commemoration and uncertainty – by Cassiane Pfund

to begin with

i wished to imagine rituals for the future

to fill a blank

to defy despair

to make celebrations and find communities

to embrace trust and name hope

an unpleasant truth is that i don’t know anymore

i don’t know where to start

nor how to (dis)continue

I don’t know

and not knowing now feels harder than ever...

but have i ever known anyway?

and you, have you ever known anyway?

what i observe from here, in switzerland, is that a certain

amount of recent art works and exhibitions, texts, research

programs and open calls is directed towards detangling,

unfolding, expanding, hacking, recreating, building, undoing,

reshaping, reinventing and designing future(s)...

but what would be

what would it sound or taste like

a future to yearn for?

00. what tongue(s)?

storytelling and underground stories have probably been an act

of resisting oppressions and uncertainties, an act of imagining

alternative solutions and gathering since human beings can

speak.

when mateo chacón pino contacted me to write a text, my

mouth felt dry as if my tongue was gone, and words were barely

present. i asked myself:

do we need more and more and more and more words?

in an attempt to grasp something from a landscape my fingers

don’t recognize most textures of

from futures that feel blurry

–unimaginable and distant, yet so close–

i sit by the river

searching sediments and pebbles for another tongue

a sensory one for

what is

what resists

what evolves

what survives

a tongue that dances

a tongue that doubts and trusts

a tongue that listens

a tongue for now

pause

gravity is what has the capacity to make bodies sink, just as

much as it allows them to be held, for as long as a ground

remains.

–in any case

we will learn to breathe

we will learn to swim

they say

who is we?

who is they?

pause

for now

close your eyes

your own flesh

merged with water

feels like the translucent one of a jellyfish

marine mammals¹

appear

marine heatwaves the moment after

and the same melody

again and again

reminding you of a sacred foundation

creatures that came before

all those who will hopefully come after

01. future(s)

if tomorrow can be understood as much as

the day after today

a period of time close to now

a few decades centuries ahead

or even when the sun explodes

–and yet probably some time before–

what future(s) are we talking about?

what is meant to be understood when the word ‘future’ is used?

is it really and only a matter of time?

and what would make future(s) possible?

I read somewhere that quantum physics and ongoing

research keep showing us how little our understanding of the

future is. fascinating enough, it feels like time perceived as

linear

tends to mimic a common representation of human life; a

chronological timeline starting with birth and ending with

death.

but is it really?

in the piece niagara 3000, the artist pamina de coulon says

le futur vient de l’amont²

future comes from upstream

pause

for now

I close my eyes

the same melody unfolds

creatures who came before

those who will come after

02. where to start?

a place to start could be causality, whilst keeping in mind the

richness and uncertainty of multifactoriality, that is,

when different factors are involved and it becomes complex to

tell which causes what and how. ie, it can be very difficult to

identify what cause(s) migraines because different elements

are, most of the time, commonly identified to

be(come) potential triggers, such as food, stress, sensory

stimulation, pollution, abuse, etc., and in many cases, they tend

to be combined. this is when a holistic vision tends to

highlight the notions of system and ecosystem.

if part of what a future to yearn for may be like partially depends

on how we, as societies, decide to take action, on what we, as

societies, decide to embody and nurture,

how to prepare the bed for such futures now?

how can we find ways through by embracing the discomfort of

uncertainty?

how can we allow ourselves to grieve, not as a sign of despair,

rather as a way of integrating the fragility of life and

reactivating our love for the earth we live on?

and again, who is we?

in her last book vivre libre³, amandine gay expresses with clarity

how the desire to transform society must be thought of as a

collective effort that starts with an intimate movement. she

writes:

we aspired to transform society without being aware

that it started with our own liberation from norms that

are productivism, competition, need for attention or

even precarity.⁴

her vision offers the chance to both come back to one’s own

situated body through decentering oneself from normativity with

a certain lucidity regarding how falling into the trap of white

supremacy–by both internalizing and reproducing its tools–needs to be talked about, not with the intention of blaming

individuals, but as a reminder of where such transformation

starts with.

03. hierarchised knowledge⁵, and bodies

in 2016, i remember an introductory class on

epistemology⁶ and the exam i wonderfully failed at. i found

myself having difficulties at engaging with the subject as the

approach was lacking something i needed, something crucial i

struggled to identify at the time. i then started to look around to

soon realize that, at the time, the department–in which i tried

to fit in not without anxiety–had a tendency to deeming itself

as a temple of knowledge whilst actually failing at

reporting on diversity of knowledge, as well as broadening

perspectives, representations and points of view.

a year later, i meet marie lefebvre–a researcher based in

montreal who i am happy to call friend– she introduced

me to both a philosophical and social practice which aims to decenter a

commonly shared view on (brain perceived)

intelligence and knowledge. such practice underlines

the necessity of both listening to–in a broad sense–and

considering every person as a potential epistemic agent in the

sense that everyone can be learned from. this vision makes

space for both a redistribution of power, and

questioning stereotypes as well as other hindrances to

legitimacy.

here are two definitions of knowledge from the merriam

webster dictionary⁷:

the circumstance or condition of apprehending truth,

fact, or reality immediately with the mind or senses.

the sum of what is known: the body of truth,

information, and principles acquired by humankind.⁷

i wonder how could coexist different modes of knowledge

acquisition without hierarchies, and beyond these very modes,

how to collectively aim towards what marie explained to me.

and what about access to knowledge?

could it be that the absence of situated bodies within such an

analytic field was a central factor of the

disconnection i experienced?

and if yes, how to value body intelligence and operate from a

common ground: we experience and feel–in our own sensitive

ways–, therefore we belong?

cultivating long term visions contributes to giving a more

consistent direction to actions and helps find meaning.

however, whilst imagining futures is crucial, it cannot be

sufficient as the act of imagining itself is intertwined with the

now⁸, and i will even say, with situated nows.

a future to yearn for won’t magically happen

without taking accountability

without dismantling any kind of supremacy

without feeling

and coming back to (our) bodies with radical honesty

04. epistemic injustice

the notion of epistemic injustice invented by miranda fricker⁹,

invites to address the question of knowledge as power. indeed,

who is perceived as contributing to the creation of knowledge

and who is not? which voices are heared, which are ignored

and which are silenced?

each time a voice is ignored and silenced,

what will be remembered from the past shrinks already, and

with it, an understanding of the present. to feel a sense of the

present(s) that is or are being lived, and project any type of

possible future, there is an essential urge to work towards

resisting separation.

like many authors and artists, wendy

delorme¹⁰ reaffirms in an interview with constant spina for censored magazine¹¹,

reaffirms separation:

nous sommes un tout : humains, arbres, montagnes,

cours d’eau et animaux. tout le monde du vivant est

interconnecté, interdépendant. c’est très simple, c’est

une évidence, et pourtant, de par nos modes de vie

d’aujourd’hui, on ne cesse de l’oublier.¹²

we are one: humans, trees, mountains, rivers

and animals. all living things are

interconnected and interdependent. it's very

simple, it's obvious, and yet, because of our

lifestyles today, we keep forgetting it.

an article on epistemic (knowledge) injustice within the field of

psychiatry research provides an understanding of the concept:

epistemic injustice is a form of systemic discrimination

relating to the creation of knowledge. it occurs when

people from marginalized groups are denied capacity

as ‘epistemic agents’ (i.e., as creators of knowledge),

and are diminished or excluded from the process of

creating meaning. such exclusion creates conditions

in which the lived experiences of marginalized people

are primarily interpreted by people who do not share

their social position.[...] as an approach, lived

experience work recognized that marginalized people

are rarely afforded the opportunity to theorize their own

experiences and generate solutions.¹³

the authors of the article mention and warn against the risk of

epistemic exploitation, which appears to be another form of

extractivism when these lived experiences are absorbed within

existing dominant structures where they become tokens¹⁴. in

reality, the question of the lived experiences, when facing

extractivism mecanisms, is deeply intertwined with colonial

thinking:

[the question of the lived experiences] has

encountered an inherent problem though in seeking

to challenge western traditional valuing of positivist

approaches to research, with their emphasis on

‘objectivity’, ‘neutrality’ and ‘distance’. these are still strong

in the psych system and have distorted our

understandings of what counts as knowledge. so, if you

have direct experience of a problem, like poverty,

distress or indeed colonisation, where such research

values apply, you can expect to be granted less credibility

and your knowledge seen as less reliable

because you are ‘too close to the problem’ – it affects you

and you cannot claim to be neutral, objective and distant

from it. thus, you can expect to be seen as an inferior

knower and your knowledge less reliable. this

means effectively that if you have experience of

discrimination and oppression you can expect

routinely to face further discrimination and be further

marginalised and devalued.¹⁵

05. sensitive knowledge

the centre d’archivage des savoirs sensibles, an art work by the

company création dans la chambre¹⁶ which connects popular

archives, knowledge(s) and memory, moved me deeply. here is

the description i found on their website:

cette installation monumentale d’archivage populaire

offerte aux citoyen-n-e-x-s deviendra en quelque sorte

un lieu d’échange poétique d’apprentissage, sans

discrimination quant à l’autorité d’un savoir sur un

autre; nous voulons proposer un espace déhiérarchisé

où tou-x-t-e-s peuvent laisser quelque chose au monde

dans une optique de transmission. que ce soit par un

enseignement artisanal unique, une chanson cachée

dans un vieux souvenir, l’histoire d’un-e-x aïeul-e-x

transmise par l’oralité, une recette familiale ancestrale

ou l’étude toute personnelle d’un comportement

animalier, chacun pourra agir sur la mémoire collective

en perpétuelle construction.

the centre d’archivage du savoir sensible highlights an

important dimension: knowledge cannot be reduced to one

single type or category. vigilance and humility are required to

avoid establishing competition or hierarchy

between one another, and be aware of where they come from

and/or were taken from.

06. lineage & commemoration

whilst i wonder what the tools to help us embody such

a change of perspective could be, commemorating visits me.

what will remain if there is no one to remember?

some weeks ago, at a round table organized by the association

afrikalab¹⁷, co-moderated by ivan larson ndenguewith germaine

acogny and shelly ohene-nyako, the notion of lineage appeared

as an essential way of both honouring and remembering who

we learned and still learn from.

commemoration is an act of togetherness

one of collective resistance

which prevents memory from being erased

a ritual to keep traces

bring them back to life for a moment

before transmitting them further

i like to see it as a cycle of honoring what came before

receiving

listening

learning

questioning

refusing

nurturing

transforming

then confiding

a cycle having its own rythms which requires

slowness and presence

awareness and proximity

being aware of what made life possible

invites us to proceed to an ongoing choreography

a movement which defies linearity

bringing ancient memories

asking to adjust

to learn

to choose what we keep honoring

what we’ll have transformed

–or tried to–

to be aware of the traces we may leave

and repeat

from where i write

and for now

this ground remains.

cassiane c. pfund (BR/CH)’s practice situates itself in the interstices. reassembling writing, art, research and poetry, it considers words as a starting point from which to explore other media such as performance, installation and publishing as sculptures and collective experiences of transmission. its wish is to open up slow spaces where people can meet, exchange stories, feel their emotions and raise questions.

cassiane c. pfund (*1993) lives in Geneva. first trained as a philosopher (ma degree, unige & uqam, 2018), they then desired to feel and deepen concepts from a body and interdisciplinary artistic perspective. (ma cap, hbk, 2020)

website: cassianepfund.ch

[1] the expression ‘marine mammals’ is borrowed from author and

researcher alexis pauline gumps and her text undrowned: black feminist

lessons learned from marine mammals, ak press (2020).

[2] niagara 3000 is a performance by artist and author pamina de

coulon from the fire of emotions saga.

[3] gay amandine, vivre libre, exister au cœur de la suprématie blanche,

cahiers libres, la découverte, october 2025.

[4] ibid., p.114.

[5] in english, the term ‘knowledge’ refers indiscriminately to both

learning and understanding, which is not the case in french.

[6] the introductory course in epistemology is a compulsory module in

philosophy studies at the university of geneva.

[7] this definition is taken from the meriam webster dictionary:

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/knowledge

[8] during her talk at the w.o.r.d. school, author and activist sarah

durieux introduced the importance of anchoring discourse in the

present when it comes to storytelling and political discourse.

[9] history records that the concept of epidemic injustice was first

formulated by philosopher miranda fricker.

[10] wendy delorme is a french author, performer, teacher, researcher

and feminist activist.

[11] censored magazine is an editorial platform where feminist ideas,

emerging creativity and transmission intersect, beyond the dominant

narratives.

[12] Ibid., constant spina (2025), interview with wendy delorme: le

roman comme un cycle de l’eau, [online].

[13] celestin okoroji, tanya mackay, dan robotham, dation beckford,

Vanessa Pinfold (2023), Epistemic injustice and mental health research:

a pragmatic approach to working with lived experience expertise,

frontiers in psychiatry, vol. 14, [online],

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.

2023.1114725/full

[14] tokenism refers to the practice whereby a group or organisation

includes people from minority backgrounds without making any real

structural changes or providing them with long-term support, as it is in

fact a case of superficial inclusion.

[15] peter beresford, diana rose (2023), decolonising global mental

health: the role of mad studies, cambridge prisms: global mental health,

cambridge university press, [online],

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/global-mental-health/article/

decolonising-global-mental-health-the-role-of-mad-studies/

EEF259FE948CAA0E25E57036D547EBFC.

[16] the centre d'archivage des savoirs sensibles is a project created by

the quebec-based company création dans la chambre:

https://www.creationdanslachambre.com/

[17] afrikalab is a venue dedicated to culture, ‘living together’,

transmission and training in the city of geneva.

The Camera Cannot Eat – by Jim Chuchu

"The Camera Cannot Eat" is a video essay that wrestles with the quandary of how to make images about African food culture when every visual choice (whether 'traditional' or 'contemporary') feeds extractive gazes built over centuries of colonial image-making.

The work uses the very materials it critiques (stock footage of Africans cooking and eating, AI-generated imagery of 'African food') to reveal how thoroughly the visual language of African food has already been captured, catalogued, and turned into data.

Rather than offering solutions, the essay stews in this tension, suggesting that what cannot be photographed, the senses of taste and smell, and the embodied experience of gathering around food, might be what remains safe, as yet unreachable by the circuits of extraction

Jim Chuchu (KE) began his artistic practice as part of Kenyan alternative music group Just a Band, creating music and visual works until 2012. His visual works have since exhibited at MoMA, the Vitra Design Museum, and as part of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art collection, while his films have screened at Berlin, Toronto, and Rotterdam international film festivals.

In 2014, Jim co-founded the Nest Collective, a multidisciplinary art collective based in Nairobi, Kenya. Their critically-acclaimed queer anthology film Stories of Our Lives won the Jury Prize at the 2015 Berlinale Teddy Awards and has screened in more than 90 countries, despite being banned in Kenya for 'promoting homosexuality'.

As part of the Nest Collective, Jim participated in the International Inventories Programme, an international research project investigating the presence of Kenyan cultural objects in global institutions. Between 2018-2021, the project catalogued more than 32,000 objects and engaged publics on urgent debates around object movement and colonial history.

Since transitioning to solo practice in 2021, Jim has composed for the Emmy-nominated Netflix documentary Hack Your Health (2024) and is a participating artist in the African Film and Media Arts Collective (AFMAC), developed by artist Julie Mehretu. He is currently directing documentary shorts as part of African in the Anthropocene, exploring African experiences of unprecedented environmental and social change, slated for release in early 2026.

His work consistently examines questions of representation, cultural sovereignty, and the politics of image-making in contemporary Africa.

The Camera Cannot Eat – by Jim Chuchu

"The Camera Cannot Eat" is a video essay that wrestles with the quandary of how to make images about African food culture when every visual choice (whether 'traditional' or 'contemporary') feeds extractive gazes built over centuries of colonial image-making.

The work uses the very materials it critiques (stock footage of Africans cooking and eating, AI-generated imagery of 'African food') to reveal how thoroughly the visual language of African food has already been captured, catalogued, and turned into data.

Rather than offering solutions, the essay stews in this tension, suggesting that what cannot be photographed, the senses of taste and smell, and the embodied experience of gathering around food, might be what remains safe, as yet unreachable by the circuits of extraction

Jim Chuchu (KE) began his artistic practice as part of Kenyan alternative music group Just a Band, creating music and visual works until 2012. His visual works have since exhibited at MoMA, the Vitra Design Museum, and as part of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art collection, while his films have screened at Berlin, Toronto, and Rotterdam international film festivals.

In 2014, Jim co-founded the Nest Collective, a multidisciplinary art collective based in Nairobi, Kenya. Their critically-acclaimed queer anthology film Stories of Our Lives won the Jury Prize at the 2015 Berlinale Teddy Awards and has screened in more than 90 countries, despite being banned in Kenya for 'promoting homosexuality'.

As part of the Nest Collective, Jim participated in the International Inventories Programme, an international research project investigating the presence of Kenyan cultural objects in global institutions. Between 2018-2021, the project catalogued more than 32,000 objects and engaged publics on urgent debates around object movement and colonial history.

Since transitioning to solo practice in 2021, Jim has composed for the Emmy-nominated Netflix documentary Hack Your Health (2024) and is a participating artist in the African Film and Media Arts Collective (AFMAC), developed by artist Julie Mehretu. He is currently directing documentary shorts as part of African in the Anthropocene, exploring African experiences of unprecedented environmental and social change, slated for release in early 2026.

His work consistently examines questions of representation, cultural sovereignty, and the politics of image-making in contemporary Africa.

Beyond Sustenance: The Subtle Art of Being A vessel – by Rebecca Khamala

There is a Luganda saying: “Oluganda kulya, olugenda enjala teluda,” which translates to “Relationship [brotherhood] is eating, the one [relationship] that goes hungry does not return.” Beyond sustenance, food is a love language. It is revered. The source of fellowship with community, with family, and with self. Food is an intimate part of our cultural heritage, often a subject in folklore, embedded in proverbs and sayings, and at the centre of our material culture.

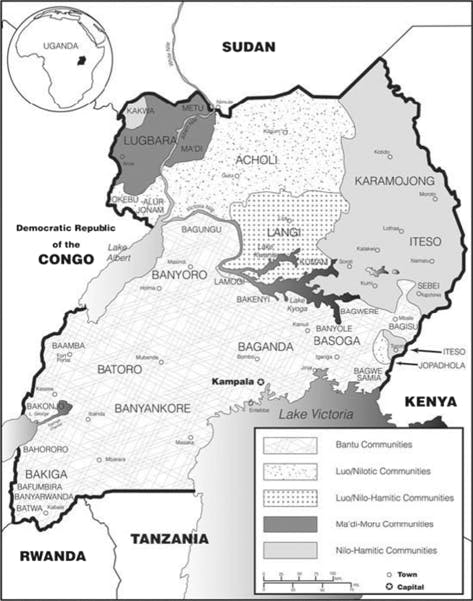

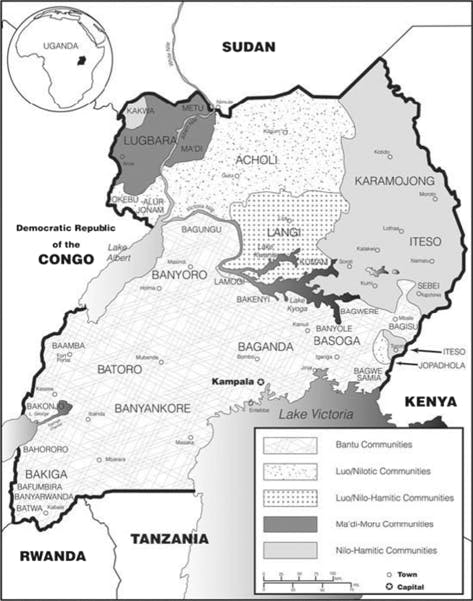

1. Construction detail of ekibbo coiled around with enjulu

In many of the communities in Uganda, food is a gift and baskets are the gift wrap. A basket is never merely a basket. It is a vessel: for serving millet, for sun drying mushrooms gathered in the morning dew, for yam carried home from the fields, for bride price gifted during okwanjula¹. They are instruments of everyday life. Just as art provides insight into culture, baskets offer a unique lens into food cultures in Uganda. Basket-making is a prominent and deeply rooted tradition in Uganda’s cultural heritage, part of a broader artistic heritage engrained in the material culture of Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi, too. As in many other African cultures, artistic expression has been an integral part of the social and cultural fabric of communities in this region. East African art prioritised utilitarian objects over figurative ones—items crafted from materials in the immediate surroundings—reflecting a harmonious blend of function and artistry, drawing inspiration from the rhythms and necessities of daily life. To appreciate this rich cultural heritage, one has to look beyond the geopolitical boundaries that are a product of colonial enterprise and instead focus on the diverse cultures and social structures that predated colonisation. Uganda alone has 56 recognised tribes, each with their own language, customs, cuisine, and material culture. And while unique to individual groups, linguistic varieties and customs reflect deep historical, geographical and cultural connections among the different communities within and across national borders.

This piece begins with the basket, not because of its rarity or ornamentation, but precisely because it is ordinary. Baskets are part of a silent choreography of life: women winnowing grain, street vendors balancing baskets of bananas on their heads, and jjajjas² sitting by the veranda coiling obukeedo into tight spirals while recounting tales of times long gone. Baskets are everyday objects, quiet archives holding stories of the land, of labour, and of life. To follow their weave is to trace the delicate, ever-shifting relationships between people, ecosystems, and food cultures in Uganda and across East Africa. Over the years I have developed a practice somewhere between art and architecture. One fueled by a deep curiosity about people, culture, and the environment. My practice is focused on performing material culture and contemporary design, where I research traditional crafts through collaborating with local artisans, and adapt them to contemporary living. In my quest to find an African, Ugandan design identity, I landed on the mundane e kibbo n'omukeekka. Items that are found in nearly every properly adorned household in Uganda. When I began investigating the materiality and form of a basket, in the hope that I could pick from what's local to inform and inspire my own design and architectural work, I found that despite the fact that I've grown up with these items, I completely had no idea about their makeshift both in material and technique. So, I started to explore. First by deconstructing. The more I put apart, the more my ignorance is made apparent to me. I didn't realise there were so many different kinds of baskets: In Buganda³ for instance, the kikapu is a palm weaved tote-bag-like shopping basket for buying goods in the market, the kisero a deep and large basket for harvesting food from the fields and sometimes used for storing food, ekiyonjo a woven cage for carrying chicken and for sheltering chicks, ekiwewa/olugali a flat tray for winnowing grain, enzibo a woven trap for catching ensonzi , and ekibbo for storing, preparing, and serving food. These baskets and more are found throughout the country, with variations in designs, and materiality that reflect local foods, food systems, and surrounding ecosystems.

1. Cultivating Rhythms of Care Kla Art 24 Installation

2. Main ethnic groups in Uganda 2001

The inquiry into baskets has also meant encountering the people that make them and interacting with the ecosystems from which their materials are acquired. Most of the baskets are traditionally woven by women: in their free time, in-between chores, alongside cultivation, and during food preparation. Traditional gender roles dictate a division of labour where women predominantly handle home chores and subsistence farming, while men focus on cash crop production and paid work. Therefore, decisions concerning food and nutrition were/are solely left to the woman and, by extension, the making of the vessels that carry the food. Baskets are woven from plants: banana fibre, papyrus, raffia, palm leaves and stalks, reeds and grasses, each chosen for its flexibility, texture, and local availability. The basket s production requires deep ecological knowledge: Knowing where a certain grass grows, when its stems are strongest, how to strip it into thread, and which plants yield colourfast dyes.

I was surprised to learn that the kibbo or ekibbo , one of the most common baskets in Uganda, is made from banana plants. It is made from obukeedo and coiled around with the outer layer of enjulu, a papyrus-like reed found in wetlands. The kibbo is primarily used for carrying food, storage, and in the preparation and serving of matooke. Matooke is a staple food in Central Uganda and is also largely consumed in Western Uganda, as well as in Rwanda and Tanzania. It is one of several indigenous varieties of the East African Highland bananas that developed in Uganda despite bananas not being native to the region itself. Matooke is prepared in a variety of ways, popularly as mashed matooke, steamed and mashed in banana leaves, a signature dish from Buganda. It is usually accompanied by a groundnut paste that can be made plainly or cooked with dried mushrooms, smoked meat, smoked fish, or malewa⁴. Matooke is also prepared as whole fingers in katogo⁵ . Bananas are also used to make omubisi⁶, made from a banana variety called embidde and which can then be fermented to make a banana brew. Other common varieties include bogoya, a dessert banana served and eaten as fruit, ndiizi, the shorter and sweeter dessert type which is normally used to make kabalagala⁷ ; gonja, plantain which is prominently roasted and sold at roadside markets, and lastly kivuuvu, a plantain variety which is fatter and slightly less sweet compared to gonja, which is usually steamed with its peelings and served alongside other carbs like yam, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, and cassava.

1.A display of different banana varieties from the Cultivating Rhythms of Care Kla Art 24 installation

2. A decorative basket from Fort Portal by Mr. Akiiki one of the facilitators for the KLA Art 24 workshops

Another intriguing case is the endiiro. It is an open topped subtly cylindrical basket with a fitted lid, made for serving millet bread common among the Batooro, and also used by the Banyankole from the Ankole⁸ tribe. Endiiro is made from millet straw, a by-product of finger millet harvest. Other tribes within the wider Rwenzori region in Western Uganda also incorporate millet stalks or straws as the core of their basket construction, which is wound over using raffia that was coloured with plant dyes sourced from nearby highlands. Finger millet is a staple amongst the Nilotic, Nilo-Hamitic and Bantu ethnic communities in Northern, Eastern, and Western Uganda, a cereal native to East Africa, which is said to have originated in the highlands of Uganda and Ethiopia. Finger millet is a nutrient dense cereal that thrives in a variety of environments and conditions making it lucrative for famine prone areas. It occupies 50% of Uganda’s cereal area, and is an integral part of cultural functions across Uganda. Millet is served at weddings, naming ceremonies, and during festivals celebrating a new harvest. It is consumed in a variety of forms, as millet bread usually accompanied by malakwang⁹ in northern Uganda; eshabwe¹⁰ and Firinda in western Uganda amongst farming and cattle-keeping communities; roasted meat in north-eastern Uganda amongst the nomadic communities; and with smoked fish in the east amongst fishing communities. Finger millet is also eaten as porridge, as a fermented drink, bushera, and as brew. Different varieties are used for specific consumption, for example amongst the Itesots from the Teso tribe the variety called emoru is preferred for making ajon, a beer used in the new harvest celebrations.

The making of both the food and the baskets is a highly physical and intuitive process. For instance, in the act of okuyubuguluza olulagala, the removal of the banana leaf stalk carefully and in a flat manner apt for cooking, one must keep the stalk intact so it can be shredded into obukeedo to construct ekibbo. This embodied knowledge has long been passed down from generation to generation, from older women to younger ones, an informal education that is increasingly shaping my practice and consequently my life. For our KLA ART project in 2024, my collaborator Birungi Kawooya and I explored how our foremothers cared for their bodies, focusing on the tale of Njabala. In it, a married and spoilt girl is guided by her mother's ghost on how to cultivate abakazi balima bati¹¹, a tenet of Ugandan culture. We analysed the emphasis of cultivation in this folklore and asked: Why was this the thing Njabala needed to learn from her mother? What does it mean to cultivate?

1. A street vendors selling beans in a variation of ekibbo

2. A variation of ekisero

Women have been custodians of invaluable nutritional and ecological knowledge for ages, understanding which foods thrive in each season, which vegetables boost iron levels, and how to nurture their bodies in alignment with their monthly cycles and the changing annual seasons. As a guide to track time, farmers observed the movement of the moon, marking the progress of months and seasons. Similarly, women often tracked their menstrual cycles using the phases of the moon. To tend to the land was to care for their own bodies. It was customary (especially in Buganda) to plant fruit trees around the home and for women to grow vegetables and prepare them daily, especially steamed in banana leaves on top of carbohydrates. That way, they ensured dietary diversity that supported their health. Growing medicinal plants around the home, especially those that support women's reproductive health, was and continues to be an essential practice. In some communities, such as among the Basoga, women were and still are forbidden from engaging in certain activities during menstruation, such as harvesting palm leaves for weaving, based on the belief that the tree could disappear. These taboos, though seemingly restrictive, were actually a form of self-care, encouraging rest and honouring the natural rhythm of the body. Through these practices our foremothers became not only stewards of the land, but guardians of its wisdom. By simultaneously attuning themselves to the natural rhythms of both land and body, they embodied a profound connection to a greater consciousness and became vessels through which its knowledge flowed.

A large portion of the vegetables in diets across East Africa are wild, and certain communities, e.g.,in the Teso-Karamoja region continue to rely on wild edible plants, especially during food scarcity periods. As our wild landscapes gradually urbanise, so too do our food systems evolve, along with the vessels that support them. We are witnessing material evolutions in traditional practices, where plastic is continuously replacing natural materials, for example the use of hard plastic strands in the production of bikapu¹² and plastic rope in place of raffia. Plastic found its way into food preparation too, notably as a covering in addition or as an alternative to ndagala¹³ used in steaming foods like matooke or maize to better preserve moisture.

This shift reflects a broader inclination toward convenience and durability, where a combination of a rapidly growing population, changing living patterns, and rapid urbanisation create opportunities for the development of food products such as matooke flour and matooke biscuits; private beverage companies increasingly taking up the commercialisation of products like bushera and mubisi. All the while industrial agriculture, deforestation and swamp reclamation destroy the natural habitats of plants that serve as source for basketry materials: Swamps are drained for construction, native grasses are vanishing under commercial agriculture, and simultaneously global food systems introduce packed imports and plastic packages dislodging the need for and knowledge of traditional basketry.