The Climate of Art

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino

I am writing these lines while a severe heat wave affects southern Europe in July, just a few weeks after the fourth edition of the foodculture days biennial took place in Vevey. The glittery lights of the sunny alpine landscape and the tender sense of community of those days are slowly fading into memory, leaving behind burning questions. While single events like this one offer brief respite, it remains difficult to fathom their impact on long-term processes such as climate change. So, how could art and culture be understood, and cultural events organized, so as to truly contribute to a sustainable human presence on earth?

In the wake of the biennial, foodculture days invited me as guest editor for the third cycle of Boca A Boca, aiming to loosely look back at the event while addressing how culture and art may contribute to a sustainable planetary society. My background as a curator in Switzerland and abroad, as well as my current doctoral research into the intellectual history of art and its relationship with ecology, shape this cycle, as does my first-hand experience of the biennial and the conversations I had in Vevey.

To you, dear reader, this cycle may appear as a collection of isolated contributions circling the contradictory relationship art maintains with environment. Each of them, however, testifies to ongoing reflections and exchanges with their authors. In this sense, they offer an insight into discussions that will hopefully continue in other outlets and that cover forays into institutional structures, aesthetic and poetic forms of time, and methodological questions of art history.

In her essay, Magali Wagner, a PhD candidate at the University of Bern who worked as a volunteer during foodculture days, reflects on her subjective experience to imagine methodological approaches able to include the voice of the ever-mutating natural world in cultural discourses.

The Netherlands-based American artist Lucy Cordes Engelman has recently been interested in developing a poetic relationship with the Arctic landscape. Her contribution is a reflection on time and consumption in the shape of a poem and images from her personal archive.

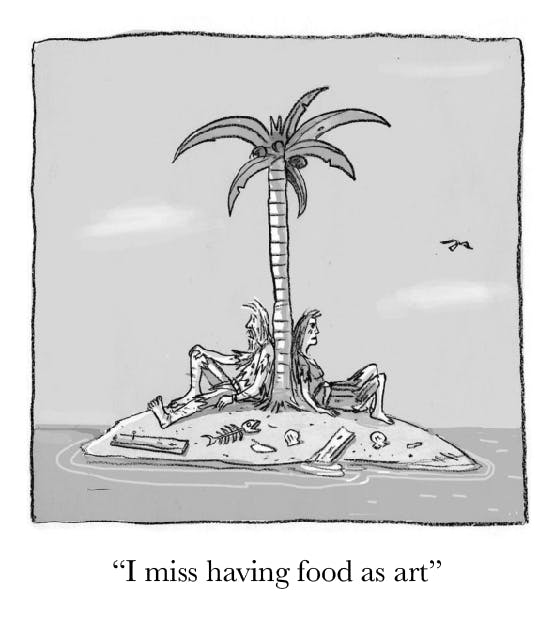

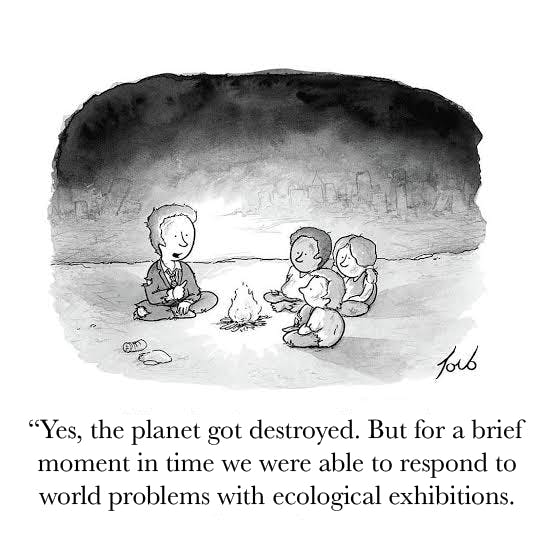

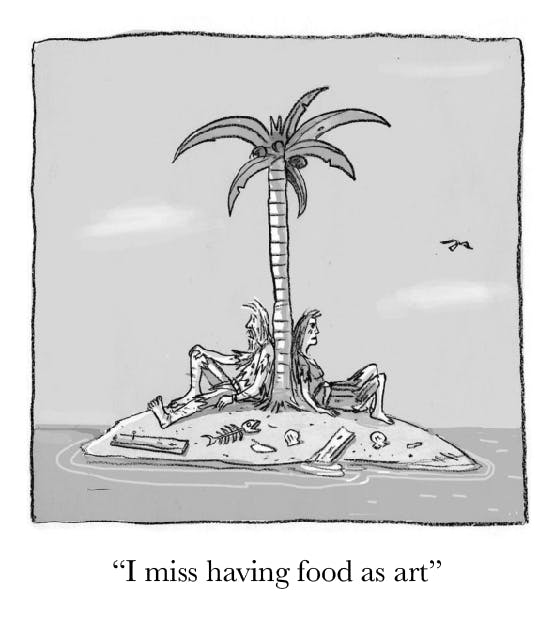

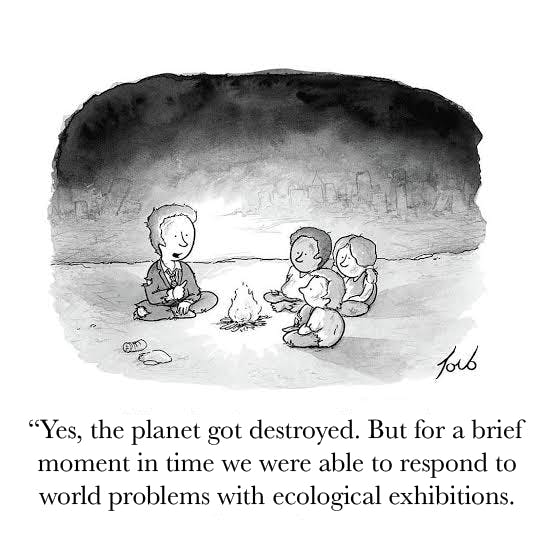

Cem A. is an artist based in Kassel, mostly known for his Instagram meme account @freeze_magazine through which he addresses the endless paradoxes, contradictions and hypocrisy at play in the art world. For Boca a Boca, he curated a series of memes specifically in response to the questions raised in this cycle and to the other contributions.

The final contribution of this cycle is a short essay by yours truly, reflecting on the vital necessity of finding a path toward a truly sustainable art and the challenges ahead, through the lens of my ongoing doctoral research and observations made during foodculture days’ biennial.

Rather than give definite answers to an evolving problem, this cycle aims to nurture preexisting conversations between contributors and myself alongside the articulation of a variety of issues we face when attempting to think of sustainable artistic formats. Taken together, the contributions offer a reflective take on the cultural and structural challenges of developing artistic projects that aim to epitomize sustainability.

The Climate of Art

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino

– Edito by Mateo Chacón Pino

I am writing these lines while a severe heat wave affects southern Europe in July, just a few weeks after the fourth edition of the foodculture days biennial took place in Vevey. The glittery lights of the sunny alpine landscape and the tender sense of community of those days are slowly fading into memory, leaving behind burning questions. While single events like this one offer brief respite, it remains difficult to fathom their impact on long-term processes such as climate change. So, how could art and culture be understood, and cultural events organized, so as to truly contribute to a sustainable human presence on earth?

In the wake of the biennial, foodculture days invited me as guest editor for the third cycle of Boca A Boca, aiming to loosely look back at the event while addressing how culture and art may contribute to a sustainable planetary society. My background as a curator in Switzerland and abroad, as well as my current doctoral research into the intellectual history of art and its relationship with ecology, shape this cycle, as does my first-hand experience of the biennial and the conversations I had in Vevey.

To you, dear reader, this cycle may appear as a collection of isolated contributions circling the contradictory relationship art maintains with environment. Each of them, however, testifies to ongoing reflections and exchanges with their authors. In this sense, they offer an insight into discussions that will hopefully continue in other outlets and that cover forays into institutional structures, aesthetic and poetic forms of time, and methodological questions of art history.

In her essay, Magali Wagner, a PhD candidate at the University of Bern who worked as a volunteer during foodculture days, reflects on her subjective experience to imagine methodological approaches able to include the voice of the ever-mutating natural world in cultural discourses.

The Netherlands-based American artist Lucy Cordes Engelman has recently been interested in developing a poetic relationship with the Arctic landscape. Her contribution is a reflection on time and consumption in the shape of a poem and images from her personal archive.

Cem A. is an artist based in Kassel, mostly known for his Instagram meme account @freeze_magazine through which he addresses the endless paradoxes, contradictions and hypocrisy at play in the art world. For Boca a Boca, he curated a series of memes specifically in response to the questions raised in this cycle and to the other contributions.

The final contribution of this cycle is a short essay by yours truly, reflecting on the vital necessity of finding a path toward a truly sustainable art and the challenges ahead, through the lens of my ongoing doctoral research and observations made during foodculture days’ biennial.

Rather than give definite answers to an evolving problem, this cycle aims to nurture preexisting conversations between contributors and myself alongside the articulation of a variety of issues we face when attempting to think of sustainable artistic formats. Taken together, the contributions offer a reflective take on the cultural and structural challenges of developing artistic projects that aim to epitomize sustainability.

We are outside - An essay by Magali Wagner

We are outside, on the shore of Vevey where the crystal-clear waters of Lake Geneva glisten under a precocious summer sun. In a simple turn of the head, a breathtaking panorama unfolds, between the UNESCO world heritage terraced vineyards of Lavaux, the vastness of the lake itself and the snow-capped mountains of the Savoy Alps on the other side.

We are a composite of artists, gastronomes, scientists, cooks, philosophers, activists, researchers, gardeners, and winemakers—or something in between—and we are assembled under a pavilion-like structure with an open kitchen and a bar. Chairs and tables are scattered around, transforming the grassed area on the lakeshore promenade into a meeting place: a restaurant, a lecture hall, a reception hall, and a performance space all at the same time. We are attending the foodculture days biennial festival in late May into early June of 2023. But we also constitute it. The festival provides a framework, a platform, a curatorial concept, a space, a point in time, an exhibition—but it is nourished by the different practices of its attendees that are gathered through an extensive programme, personal exchanges and the generous work of volunteers that engage in hospitality tasks.

People come and go, engage and seclude themselves, absorb information and consume a meal, enjoy the view and go for a swim or a stroll to visit parts of the festival that are dispersed throughout the city. Everyone talks about their respective field of practice but in reaching out to others, in partaking in this festival that is meant to bridge, in exchanging, it becomes clear that everyone searches in fact for the in-betweens, the assemblages and paths towards a seemingly dystopic future. In the wake of climate breakdowns, collaboration, connection and conviviality appear to be the only antidote.

A Collective Digestion: INLAND Academy, foodculture days 2023

As a trained art historian participating as a researcher and as a volunteer, this made me reflect on several aspects of my practice. Let me give you a personal note. After getting in contact with the project through different events that were carried out in 2022 and having established personal connections, I participated with the goal to include foodculture days as my first case study in my PhD thesis, intendeding to absorb and document everything. I rented an apartment for the duration of the festival and signed up for the volunteering programme. I was dedicated and ready. And I was immediately overwhelmed by the radical relational character of the act of eating, by the intensity and immediacy of social interactions, the simultaneity of events, and more personal questions of who and where I want to be in the world.

Quickly, I abandoned my urge to document everything and fully immersed myself. As personal connections grew, I was able to ease into the unfolding days and, during my volunteer shifts, I was surprised to realise how much I used to enjoy and clearly missed the physical and mental activities of hosting, waitressing, and catering. Introducing myself repeatedly in different encounters and describing my practice and interests in sometimes brief and at other times extensive conversations turned out to be a reflection on how my ways of thinking and acting were formed over the years. Toward the end, I remember laying on a bench listening to Maya Minder’s stimulating lecture on her artistic research on seaweed. Overwhelmed with information and impressions, I was not able to perform my scientific routine: to sit up straight and take notes. As the screen was almost invisible from the sun, I allowed myself to simply listen to my body, to lay down, take mental notes and have an embodied experience of what it means to be part of a collective consciousness. Some people were cooking, others were cleaning dishes, some coming back from swimming, some were lying down drawing, some were sitting up intently taking notes. Snippets evaporated into everyone’s ears, triggered memories or associations, mixing with the noises of gastronomy and incipient summer at the lakeside. An earlier realization during a conversation helped me ease: I found that I am more interested in the general flow and overall structure of the event than in every single contribution and detail.

Aux Complices & Maya Minder, foodculture days 2023

During my art history studies, I learned associative thinking and a criticality towards historical narratives, to see connections—between people, objects, historical continuities, regions, different areas of life—and to reflect on privileges and blind spots. I focused on decolonial museology and was thinking in depth about how museums and object categories came along, why we, in Euro-Western thought, developed a cultural practice of (supposedly) autonomous art, all the while I was simultaneously working in gastronomy since I had turned 18. I wrote my master’s thesis on Adrian Piper’s 2018 retrospective at MoMA in New York and her activities in the field of art, philosophy and yoga, which she describes as practices rather than mere theoretical occupations that intersect and inform each other. This perspective influenced me in becoming daring to connect different interests and areas of my life without regard for the conventions of the respective fields. Art, to me, is a tool, a philosophical one, as well as a social practice to reflect and meditate about our being and acting in the world. It can enable activism and socio-political engagement to challenge hegemonic power structures but it can also be a rather intimate way to discover which aspects, questions, or circumstances move a person so much that they create something sensually perceptible in the world.

Nicolas Darnauguilhem (La Pinte des Mossettes), foodculture days 2023

I am currently part of an academic project connecting art and culture to ecological questions which allows me to bridge my professional becoming to core memories from my early childhood. Growing up in an environmentally aware household that was concerned with food politics within the German eco-movement as well as emphasising French culture around the quality of food informs my current research interest in art forms that bridge agroecology and food politics. Through these practices, I am concerned with the climate emergency, environmental justice and interspecies connections, and how to facilitate these concerns and practices through institutional structures and curatorial practices. My realization at the festival was that vital and holistic forms of living, creating and being in the world – be it artistic, academic, or institutional – don’t fit in rigid time regimes and evade the event logics of temporal projects.

"First, socio-historical critiques of temporality expose how different societies and epochs foster different experiences of time. Looking at temporality from the perspective of everyday experience shows that time is not an abstract category, nor just an atmosphere, but a lived, embodied, historically and socially situated experience. Time is not a given, it is not that we have or do not have time, but that what we make it through practices. Temporality is not just imposed by an epoch or a dominant paradigm, but rather made through socio-technical arrangements and everyday practices. So, if we accept the possibility of a diversity of practices and ontologies, the progressive, productionist and restless temporal regime, although dominant, cannot be the only one." ¹

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

As mentioned above, I think intensely about institutional structures within the cultural field, and how museum collections and scientific disciplines emerged, mainly to understand the framework that defines our cultural practice around making art. The museum is conceived to preserve and transcend time, directly linked to European historiography which emerged in the 18th century during the Enlightenment. The perception of one’s own present as the end of a positive development is structured linearly as a narrative of progress. In order to tell this form of history with objects, the institution is conceptually based on principles of categorization, discrimination, and separation to organize a seemingly chaotic world. Its practice of accumulating, handling, exhibiting and taking care of objects in a very particular timely order of permanence speaks volumes about the Euro-modern definition of objects as dead and passive. Part of the decolonial discourse in museology is exactly that this does not comply with other cosmovisions, where the distinction between humans and their surroundings is non-hierarchical, and objects are part of a shared living and animated world. Both the institution and the hegemonic timeline of a technoscientific world that associates future with progress are modern paradigms that are nowadays called into question by the environmental crisis: the future is uncertain and the Euro-Western world slowly becomes aware of the cyclical and intricately entangled nature of micro- and macro-networks that make up our world systems.

"We are facing modern problems for which there are no longer modern solutions. […] the crisis is the crisis of a particular world or set of world-making practices, the dominant form of Euro-modernity (capitalist, rationalist, liberal, secular, patriarchal, white, or what have you), or, […] the OWW [One-World World (Law 2011)] – the world that has arrogated for itself the right to be ‘the’ world, subjecting all other worlds to its own terms or, worse, to nonexistence. If the crisis is largely caused by this OWW ontology, it follows that addressing the crisis implies transitioning towards the pluriverse." ²

Arturo Escobar

The pluriverse is defined as a world where many worlds fit in, where countless and diverse systems and locally rooted practices intersect and exist in sync with one another³. foodculture days created exactly a pluriverse during the days of its festival: the open pavilion-like structure at Vevey’s promenade, exposed to the weather, hosted different practices, different species and elements. It allowed for processes to unfold in various rhythms. We overlapped, paralleled, intersected, followed, and echoed each other, we dispersed through the city, including restaurants, cafes, museums, public and agricultural spaces. After all, we are living matter, part of a living world. Meditating about food practices makes that perfectly clear: when we zoom into the metabolizing processes of our bodies and that of other species, truly immersing and defining ourselves as part of the cyclical nature of death and decay within a foodweb, we get a glimpse of the ever-evolving character of living matter and our entanglements with a vital material world. Maya Minder’s lecture was enriched by her companion, an 18-year-old spirulina kefir that travels with her. These microorganisms involved in the fermentation process created, within days, a nutrient-rich drink, generously offered to us to consume. Under the guidance of Domingo Club, other participants became hosts to grow mycelia with their own body temperature to ferment soybeans into tempeh by wearing a necklace for several days.

Grow mycelium with your own energy - Domingo Club, foodculture days 2023

"As both a cultural practice and field of academic study, gastronomy orientates itself to the deceptively simple question of how can we eat well? […] it is a relational and performative space that begets ethical, as well as gastronomic, questions about the best way to approach one another. A generous table is one that is welcoming to diverse others. […] The notion of conviviality is one that can be quite useful in thinking through the political and ethical issues of eating. […] In other words, how might a focus on conviviality enable the cultivation of a more ethical approach to the lives of other species with whom we share this planet, and how might this enrich us gastronomically? […] Food is, after all, the material embodiment of an incredibly complex but largely invisible assemblage of trophic encounters between different species. Living things do not become part of the food chain without human, animal, insect, fungus, or microorganism to absorb, break down and ultimately digest them in a continuous process of destruction, decay, nourishment and regeneration."⁴

Kelly Donati

Shapes of man’oushee - Christian Sleiman, foodculture days 2023

Including living matter in cultural formats requires truly embracing the fact that living matter is not conservable as it is ever-evolving in its form and thus requires specific formats that are open to a diversity of timelines. As a cultural event, foodculture days is far more than a ten-day long festival, occurring every second year. To me, its structure is one of the most interesting formats attempting to operate on different timelines. Ongoing field research and small-scale projects all year round, an online editorial platform understood as a living archive that follows a seasonal rhythm, and the fostering of organic, longstanding relations and collaborations with practitioners that are rooted in the local context of Vevey (farmers, cooks, gastronomes, winemakers, activists and gardeners) but are also globally interconnected (artists, scientists, philosophers, researchers), provide a platform—understood in the broadest sense of institutional framing—for multiple co-creative acts that are growing into each other, from each other and with each other. The festival, then, is only the culmination of this ever-evolving process.

This year, foodculture days’ curatorial concept—“Devouring the Soil’s Words”—bridges the discourse of artistic and gastronomic practices with agricultural practices of soil care and ontological questions of human-soil relations. Mirroring the discourse around museum temporality and distinction between active and passive modes of being, industrial agricultural practices are driven by the same progressive, productionist and restless mode of technoscientific intervention and approach soils as a (dead) resource for value extraction and (passive) object of scientific inquiry. Ecological soil care, on the contrary, approaches exhausted soils as endangered living worlds and is attentive towards micro- and macro-timescales of multispecies ecosystems.

Exhibition Sobremesa - Brigham Becker at Celeste, foodculture days 2023

"Soil is created through a combination of geological processes taking thousands of years to break down rock and by relatively shorter ecological cycles by which organisms and plants, as well as humans growing food, break down materials that contribute to renewing the topsoil. In an epoch being named ‘the anthropocene’ to alert us to the impact of human technoscientific progress on the planet or ‘the capitalocene’ to reflect the effects of capitalist politics, drawing attention to the temporal diversity and significance of more-than-human experiences and timescales has ethico-political, practical and affective implications. Here, focusing on experiences of soil care as an involvement with the temporal rhythms of more than human worlds troubles the anthropocentric traction of predominant timescales."⁵

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

I was trained to describe passive objects, temporary but finite exhibitions, and to value historical distance for better analysis. Now, I am simultaneously confronted with and part of the living cultural format that is foodculture days. It is impossible to describe every aspect in hindsight, it is evolving in form and format and points towards the future. To situate myself as part of a living network means to learn from practices that were developed to do so. In tending to the multispecies worlds that compose soils, permacultural practices of soil care might teach me how a lively form of multispecies curating in the cultural field could look like. And for that, I need to be outside first—in the fields, open-air cafes and at the lakeside of Vevey.

Pomo D’Orographies II: a counter-cartography for Vevey - Francesca Paola Beltrame, visiting Praz Bonjour - foodculture days 2023

References

¹ de la Bellacasa, Maria Puig. “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity Pace of Care.” Social studies of science 45.5 (2015): 691–716 (Web version: 1-26), here: 4.

² Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse : Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018, 67f.

³ Salleh, Ariel et al. Pluriverse : a Post-Development Dictionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2019.

⁴ Donati, Kelly. «The Convivial Table: Imagining Ethical Relations Through Multispecies Gastronomy.» The Aristologist: An Antipodean Journal of Food History 4 (2014): 127–143, here: 127–130.

⁵ de la Bellacasa, Maria Puig. “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity Pace of Care.” Social studies of science 45.5 (2015): 691–716 (Web version: 1-26), here: 5.

Pictures

© foodculture days 2023 « Devouring the soil’s words » by Beatrice Zerbato

Magali Wagner

Magali Wagner is an art historian, curator, and cultural practitioner with a background in museology, comparative cultural studies, and exhibition analysis. During her studies at the University of Bonn, she co-curated several exhibitions as scientific assistant, was engaged in various art mediation projects, worked as studio assistant and was part of the FLOORPLAN museum research network. Currently, she is PhD-candidate in the SNSF research project “Mediating the Ecological Imperative: Modes and Formats of Engagement” at the University of Bern (2021-24), an interdisciplinary and international joint project that focuses on the visual politics of climate change, the role of ecological issues in art and literature, and social engagement with the environment in indigenous cultures. In her dissertation project she examines contemporary art making practices that address questions of food production, consumption, and politics in regard to the climate crisis with a special focus on the institutional space where the cultural field intertwines with that of food production.

We are outside - An essay by Magali Wagner

We are outside, on the shore of Vevey where the crystal-clear waters of Lake Geneva glisten under a precocious summer sun. In a simple turn of the head, a breathtaking panorama unfolds, between the UNESCO world heritage terraced vineyards of Lavaux, the vastness of the lake itself and the snow-capped mountains of the Savoy Alps on the other side.

We are a composite of artists, gastronomes, scientists, cooks, philosophers, activists, researchers, gardeners, and winemakers—or something in between—and we are assembled under a pavilion-like structure with an open kitchen and a bar. Chairs and tables are scattered around, transforming the grassed area on the lakeshore promenade into a meeting place: a restaurant, a lecture hall, a reception hall, and a performance space all at the same time. We are attending the foodculture days biennial festival in late May into early June of 2023. But we also constitute it. The festival provides a framework, a platform, a curatorial concept, a space, a point in time, an exhibition—but it is nourished by the different practices of its attendees that are gathered through an extensive programme, personal exchanges and the generous work of volunteers that engage in hospitality tasks.

People come and go, engage and seclude themselves, absorb information and consume a meal, enjoy the view and go for a swim or a stroll to visit parts of the festival that are dispersed throughout the city. Everyone talks about their respective field of practice but in reaching out to others, in partaking in this festival that is meant to bridge, in exchanging, it becomes clear that everyone searches in fact for the in-betweens, the assemblages and paths towards a seemingly dystopic future. In the wake of climate breakdowns, collaboration, connection and conviviality appear to be the only antidote.

A Collective Digestion: INLAND Academy, foodculture days 2023

As a trained art historian participating as a researcher and as a volunteer, this made me reflect on several aspects of my practice. Let me give you a personal note. After getting in contact with the project through different events that were carried out in 2022 and having established personal connections, I participated with the goal to include foodculture days as my first case study in my PhD thesis, intendeding to absorb and document everything. I rented an apartment for the duration of the festival and signed up for the volunteering programme. I was dedicated and ready. And I was immediately overwhelmed by the radical relational character of the act of eating, by the intensity and immediacy of social interactions, the simultaneity of events, and more personal questions of who and where I want to be in the world.

Quickly, I abandoned my urge to document everything and fully immersed myself. As personal connections grew, I was able to ease into the unfolding days and, during my volunteer shifts, I was surprised to realise how much I used to enjoy and clearly missed the physical and mental activities of hosting, waitressing, and catering. Introducing myself repeatedly in different encounters and describing my practice and interests in sometimes brief and at other times extensive conversations turned out to be a reflection on how my ways of thinking and acting were formed over the years. Toward the end, I remember laying on a bench listening to Maya Minder’s stimulating lecture on her artistic research on seaweed. Overwhelmed with information and impressions, I was not able to perform my scientific routine: to sit up straight and take notes. As the screen was almost invisible from the sun, I allowed myself to simply listen to my body, to lay down, take mental notes and have an embodied experience of what it means to be part of a collective consciousness. Some people were cooking, others were cleaning dishes, some coming back from swimming, some were lying down drawing, some were sitting up intently taking notes. Snippets evaporated into everyone’s ears, triggered memories or associations, mixing with the noises of gastronomy and incipient summer at the lakeside. An earlier realization during a conversation helped me ease: I found that I am more interested in the general flow and overall structure of the event than in every single contribution and detail.

Aux Complices & Maya Minder, foodculture days 2023

During my art history studies, I learned associative thinking and a criticality towards historical narratives, to see connections—between people, objects, historical continuities, regions, different areas of life—and to reflect on privileges and blind spots. I focused on decolonial museology and was thinking in depth about how museums and object categories came along, why we, in Euro-Western thought, developed a cultural practice of (supposedly) autonomous art, all the while I was simultaneously working in gastronomy since I had turned 18. I wrote my master’s thesis on Adrian Piper’s 2018 retrospective at MoMA in New York and her activities in the field of art, philosophy and yoga, which she describes as practices rather than mere theoretical occupations that intersect and inform each other. This perspective influenced me in becoming daring to connect different interests and areas of my life without regard for the conventions of the respective fields. Art, to me, is a tool, a philosophical one, as well as a social practice to reflect and meditate about our being and acting in the world. It can enable activism and socio-political engagement to challenge hegemonic power structures but it can also be a rather intimate way to discover which aspects, questions, or circumstances move a person so much that they create something sensually perceptible in the world.

Nicolas Darnauguilhem (La Pinte des Mossettes), foodculture days 2023

I am currently part of an academic project connecting art and culture to ecological questions which allows me to bridge my professional becoming to core memories from my early childhood. Growing up in an environmentally aware household that was concerned with food politics within the German eco-movement as well as emphasising French culture around the quality of food informs my current research interest in art forms that bridge agroecology and food politics. Through these practices, I am concerned with the climate emergency, environmental justice and interspecies connections, and how to facilitate these concerns and practices through institutional structures and curatorial practices. My realization at the festival was that vital and holistic forms of living, creating and being in the world – be it artistic, academic, or institutional – don’t fit in rigid time regimes and evade the event logics of temporal projects.

"First, socio-historical critiques of temporality expose how different societies and epochs foster different experiences of time. Looking at temporality from the perspective of everyday experience shows that time is not an abstract category, nor just an atmosphere, but a lived, embodied, historically and socially situated experience. Time is not a given, it is not that we have or do not have time, but that what we make it through practices. Temporality is not just imposed by an epoch or a dominant paradigm, but rather made through socio-technical arrangements and everyday practices. So, if we accept the possibility of a diversity of practices and ontologies, the progressive, productionist and restless temporal regime, although dominant, cannot be the only one." ¹

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

As mentioned above, I think intensely about institutional structures within the cultural field, and how museum collections and scientific disciplines emerged, mainly to understand the framework that defines our cultural practice around making art. The museum is conceived to preserve and transcend time, directly linked to European historiography which emerged in the 18th century during the Enlightenment. The perception of one’s own present as the end of a positive development is structured linearly as a narrative of progress. In order to tell this form of history with objects, the institution is conceptually based on principles of categorization, discrimination, and separation to organize a seemingly chaotic world. Its practice of accumulating, handling, exhibiting and taking care of objects in a very particular timely order of permanence speaks volumes about the Euro-modern definition of objects as dead and passive. Part of the decolonial discourse in museology is exactly that this does not comply with other cosmovisions, where the distinction between humans and their surroundings is non-hierarchical, and objects are part of a shared living and animated world. Both the institution and the hegemonic timeline of a technoscientific world that associates future with progress are modern paradigms that are nowadays called into question by the environmental crisis: the future is uncertain and the Euro-Western world slowly becomes aware of the cyclical and intricately entangled nature of micro- and macro-networks that make up our world systems.

"We are facing modern problems for which there are no longer modern solutions. […] the crisis is the crisis of a particular world or set of world-making practices, the dominant form of Euro-modernity (capitalist, rationalist, liberal, secular, patriarchal, white, or what have you), or, […] the OWW [One-World World (Law 2011)] – the world that has arrogated for itself the right to be ‘the’ world, subjecting all other worlds to its own terms or, worse, to nonexistence. If the crisis is largely caused by this OWW ontology, it follows that addressing the crisis implies transitioning towards the pluriverse." ²

Arturo Escobar

The pluriverse is defined as a world where many worlds fit in, where countless and diverse systems and locally rooted practices intersect and exist in sync with one another³. foodculture days created exactly a pluriverse during the days of its festival: the open pavilion-like structure at Vevey’s promenade, exposed to the weather, hosted different practices, different species and elements. It allowed for processes to unfold in various rhythms. We overlapped, paralleled, intersected, followed, and echoed each other, we dispersed through the city, including restaurants, cafes, museums, public and agricultural spaces. After all, we are living matter, part of a living world. Meditating about food practices makes that perfectly clear: when we zoom into the metabolizing processes of our bodies and that of other species, truly immersing and defining ourselves as part of the cyclical nature of death and decay within a foodweb, we get a glimpse of the ever-evolving character of living matter and our entanglements with a vital material world. Maya Minder’s lecture was enriched by her companion, an 18-year-old spirulina kefir that travels with her. These microorganisms involved in the fermentation process created, within days, a nutrient-rich drink, generously offered to us to consume. Under the guidance of Domingo Club, other participants became hosts to grow mycelia with their own body temperature to ferment soybeans into tempeh by wearing a necklace for several days.

Grow mycelium with your own energy - Domingo Club, foodculture days 2023

"As both a cultural practice and field of academic study, gastronomy orientates itself to the deceptively simple question of how can we eat well? […] it is a relational and performative space that begets ethical, as well as gastronomic, questions about the best way to approach one another. A generous table is one that is welcoming to diverse others. […] The notion of conviviality is one that can be quite useful in thinking through the political and ethical issues of eating. […] In other words, how might a focus on conviviality enable the cultivation of a more ethical approach to the lives of other species with whom we share this planet, and how might this enrich us gastronomically? […] Food is, after all, the material embodiment of an incredibly complex but largely invisible assemblage of trophic encounters between different species. Living things do not become part of the food chain without human, animal, insect, fungus, or microorganism to absorb, break down and ultimately digest them in a continuous process of destruction, decay, nourishment and regeneration."⁴

Kelly Donati

Shapes of man’oushee - Christian Sleiman, foodculture days 2023

Including living matter in cultural formats requires truly embracing the fact that living matter is not conservable as it is ever-evolving in its form and thus requires specific formats that are open to a diversity of timelines. As a cultural event, foodculture days is far more than a ten-day long festival, occurring every second year. To me, its structure is one of the most interesting formats attempting to operate on different timelines. Ongoing field research and small-scale projects all year round, an online editorial platform understood as a living archive that follows a seasonal rhythm, and the fostering of organic, longstanding relations and collaborations with practitioners that are rooted in the local context of Vevey (farmers, cooks, gastronomes, winemakers, activists and gardeners) but are also globally interconnected (artists, scientists, philosophers, researchers), provide a platform—understood in the broadest sense of institutional framing—for multiple co-creative acts that are growing into each other, from each other and with each other. The festival, then, is only the culmination of this ever-evolving process.

This year, foodculture days’ curatorial concept—“Devouring the Soil’s Words”—bridges the discourse of artistic and gastronomic practices with agricultural practices of soil care and ontological questions of human-soil relations. Mirroring the discourse around museum temporality and distinction between active and passive modes of being, industrial agricultural practices are driven by the same progressive, productionist and restless mode of technoscientific intervention and approach soils as a (dead) resource for value extraction and (passive) object of scientific inquiry. Ecological soil care, on the contrary, approaches exhausted soils as endangered living worlds and is attentive towards micro- and macro-timescales of multispecies ecosystems.

Exhibition Sobremesa - Brigham Becker at Celeste, foodculture days 2023

"Soil is created through a combination of geological processes taking thousands of years to break down rock and by relatively shorter ecological cycles by which organisms and plants, as well as humans growing food, break down materials that contribute to renewing the topsoil. In an epoch being named ‘the anthropocene’ to alert us to the impact of human technoscientific progress on the planet or ‘the capitalocene’ to reflect the effects of capitalist politics, drawing attention to the temporal diversity and significance of more-than-human experiences and timescales has ethico-political, practical and affective implications. Here, focusing on experiences of soil care as an involvement with the temporal rhythms of more than human worlds troubles the anthropocentric traction of predominant timescales."⁵

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa

I was trained to describe passive objects, temporary but finite exhibitions, and to value historical distance for better analysis. Now, I am simultaneously confronted with and part of the living cultural format that is foodculture days. It is impossible to describe every aspect in hindsight, it is evolving in form and format and points towards the future. To situate myself as part of a living network means to learn from practices that were developed to do so. In tending to the multispecies worlds that compose soils, permacultural practices of soil care might teach me how a lively form of multispecies curating in the cultural field could look like. And for that, I need to be outside first—in the fields, open-air cafes and at the lakeside of Vevey.

Pomo D’Orographies II: a counter-cartography for Vevey - Francesca Paola Beltrame, visiting Praz Bonjour - foodculture days 2023

References

¹ de la Bellacasa, Maria Puig. “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity Pace of Care.” Social studies of science 45.5 (2015): 691–716 (Web version: 1-26), here: 4.

² Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse : Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018, 67f.

³ Salleh, Ariel et al. Pluriverse : a Post-Development Dictionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2019.

⁴ Donati, Kelly. «The Convivial Table: Imagining Ethical Relations Through Multispecies Gastronomy.» The Aristologist: An Antipodean Journal of Food History 4 (2014): 127–143, here: 127–130.

⁵ de la Bellacasa, Maria Puig. “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity Pace of Care.” Social studies of science 45.5 (2015): 691–716 (Web version: 1-26), here: 5.

Pictures

© foodculture days 2023 « Devouring the soil’s words » by Beatrice Zerbato

Magali Wagner

Magali Wagner is an art historian, curator, and cultural practitioner with a background in museology, comparative cultural studies, and exhibition analysis. During her studies at the University of Bonn, she co-curated several exhibitions as scientific assistant, was engaged in various art mediation projects, worked as studio assistant and was part of the FLOORPLAN museum research network. Currently, she is PhD-candidate in the SNSF research project “Mediating the Ecological Imperative: Modes and Formats of Engagement” at the University of Bern (2021-24), an interdisciplinary and international joint project that focuses on the visual politics of climate change, the role of ecological issues in art and literature, and social engagement with the environment in indigenous cultures. In her dissertation project she examines contemporary art making practices that address questions of food production, consumption, and politics in regard to the climate crisis with a special focus on the institutional space where the cultural field intertwines with that of food production.

Feed the hungry ghosts when they come for dinner

– a poem by Lucy Cordes Engelman

– a poem by Lucy Cordes Engelman

Feed the hungry ghosts when they come for dinner —

Lucy Cordes Engelman

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

Somehow that night we reheated the leftovers, cooked the tv dinner in the broken microwave, revived the stale bread in the oven with drops of water, twisted off the lid of the 10 year old can of tuna, cracked open the jar of beans that sat far back on the pantry shelf, and ripped apart the ancient bag of rice, pouring it into the rusty pot to boil. And we licked peanut butter off the knife as the moon rose (only we couldn’t see it clearly because of the clouds) and pulled oranges out of the waves, as we inhaled seeds of sadness and seeds of love.

Later we fed each other every single duck egg we could find – and also devoured the mint chocolate chip ice cream even though it had a bad case of freezer burn and then ate the soft vanilla wafers and burnt graham crackers that still tasted of smoke. By then it was already 3am but I was still strongly longing for kiwis so I settled for drinking a juniper liquor our Dutch neighbor claimed to have invented.

And seventeen years passed; the number of years it takes the “Magicicada Septendecim” 17-year-cicada to sleep before it wakes and sings again.

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

Then one morning we split a granola bar three ways, and ate a packet of instant oatmeal mixed together with hot hot honey from the hot hot springs and we poured a jar of salt onto the grass and made a perfect circle of apples around our tent and strung up popcorn in the trees and pulled up the weeds to make a salad. But don’t worry, we only grabbed some of the weeds, the others we left to multiply.

Hours passed in the afternoon as we planted ice cubes in the riverbed, sowed amaranth all over the gravel road, and foraged for smoked almonds and dumplings and saltine crackers in the valley. Someone made a necklace of nectarine pits and crowned three of us King as we drank milk (cow’s, I think it was?) to celebrate while the faucet in the forest dripped with red wine and when I lay down for a short rest wild salmon swam into my open mouth. Later, we gorged on violets dipped in moldy jam, our stomachs so full and bloated by now that we belched out melodies in a minor key and moaned in simple droning tones, rejoicing in our ability to do so.

And over the course of three more years the dorado catfish spawned in the river, beginning its journey at the headwaters and drifting thousands of miles towards the estuary in the east, eventually making its way back through the floodplains.

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

But as the sun went down this very evening, a fox wandered off with my tongue – she made me good promises – and my teeth became little pearls and then I could only eat the mud after that, but also breast milk and sour candy and all the other glorious gifts that angels whisper of.

This is how we feed our souls, they said.

And of course, you already know that in some untold amount of time

my soul will be the food that some other being is fed to be sustained,

my mouth consumed by some other mouth.

Lucy Cordes Engelmann

Lucy Cordes Engelman is an artist based in Amsterdam originally from Washington DC. She works with the sensorial potential of film and writing in relation to feminism and ecology as a way of reconnecting to the living earth. Subjugated and alternative knowledges that are deeply embedded in place are central to Lucy’s research-based practice. Graduating with honors from the MA Artistic Research KABK in 2019, she has shared work in Europe and the Americas and has an upcoming show in Seoul.

Feed the hungry ghosts when they come for dinner

– a poem by Lucy Cordes Engelman

– a poem by Lucy Cordes Engelman

Feed the hungry ghosts when they come for dinner —

Lucy Cordes Engelman

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

Somehow that night we reheated the leftovers, cooked the tv dinner in the broken microwave, revived the stale bread in the oven with drops of water, twisted off the lid of the 10 year old can of tuna, cracked open the jar of beans that sat far back on the pantry shelf, and ripped apart the ancient bag of rice, pouring it into the rusty pot to boil. And we licked peanut butter off the knife as the moon rose (only we couldn’t see it clearly because of the clouds) and pulled oranges out of the waves, as we inhaled seeds of sadness and seeds of love.

Later we fed each other every single duck egg we could find – and also devoured the mint chocolate chip ice cream even though it had a bad case of freezer burn and then ate the soft vanilla wafers and burnt graham crackers that still tasted of smoke. By then it was already 3am but I was still strongly longing for kiwis so I settled for drinking a juniper liquor our Dutch neighbor claimed to have invented.

And seventeen years passed; the number of years it takes the “Magicicada Septendecim” 17-year-cicada to sleep before it wakes and sings again.

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

Then one morning we split a granola bar three ways, and ate a packet of instant oatmeal mixed together with hot hot honey from the hot hot springs and we poured a jar of salt onto the grass and made a perfect circle of apples around our tent and strung up popcorn in the trees and pulled up the weeds to make a salad. But don’t worry, we only grabbed some of the weeds, the others we left to multiply.

Hours passed in the afternoon as we planted ice cubes in the riverbed, sowed amaranth all over the gravel road, and foraged for smoked almonds and dumplings and saltine crackers in the valley. Someone made a necklace of nectarine pits and crowned three of us King as we drank milk (cow’s, I think it was?) to celebrate while the faucet in the forest dripped with red wine and when I lay down for a short rest wild salmon swam into my open mouth. Later, we gorged on violets dipped in moldy jam, our stomachs so full and bloated by now that we belched out melodies in a minor key and moaned in simple droning tones, rejoicing in our ability to do so.

And over the course of three more years the dorado catfish spawned in the river, beginning its journey at the headwaters and drifting thousands of miles towards the estuary in the east, eventually making its way back through the floodplains.

A mouth is a door, a gateway, a portal.

But as the sun went down this very evening, a fox wandered off with my tongue – she made me good promises – and my teeth became little pearls and then I could only eat the mud after that, but also breast milk and sour candy and all the other glorious gifts that angels whisper of.

This is how we feed our souls, they said.

And of course, you already know that in some untold amount of time

my soul will be the food that some other being is fed to be sustained,

my mouth consumed by some other mouth.

Lucy Cordes Engelmann

Lucy Cordes Engelman is an artist based in Amsterdam originally from Washington DC. She works with the sensorial potential of film and writing in relation to feminism and ecology as a way of reconnecting to the living earth. Subjugated and alternative knowledges that are deeply embedded in place are central to Lucy’s research-based practice. Graduating with honors from the MA Artistic Research KABK in 2019, she has shared work in Europe and the Americas and has an upcoming show in Seoul.

The Climate of Memes

Courtesy of Cem A. also known as @freeze_magazine

Cem A.

Cem A. is an artist with a background in anthropology. He is known for running the art meme page @freeze_magazine and for his site-specific installations. His work explores topics such as survival and alienation in the art world, often through a hyper-reflexive lens and collaborative projects. He is an artistic advisor to documenta Institut.

Cem A.’s selected solo exhibitions and installations include Louisiana Museum, Barbican Centre, Berlinische Galerie, Grimmwelt Museum and Museum Wiesbaden. His group exhibitions include documenta fifteen and 14. Biennial of Young Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Skopje. He has held lectures at Royal College of Art, Central Saint Martins, Haus der Elektronischen Künste, HDK Valand, Universität der Künste and Istanbul Modern. He is a member of Hœr NY, a feminist queer and bisexual lesbian art collective founded with Harley Aussoleil and Frances Breden.

The Climate of Memes

Courtesy of Cem A. also known as @freeze_magazine

Cem A.

Cem A. is an artist with a background in anthropology. He is known for running the art meme page @freeze_magazine and for his site-specific installations. His work explores topics such as survival and alienation in the art world, often through a hyper-reflexive lens and collaborative projects. He is an artistic advisor to documenta Institut.

Cem A.’s selected solo exhibitions and installations include Louisiana Museum, Barbican Centre, Berlinische Galerie, Grimmwelt Museum and Museum Wiesbaden. His group exhibitions include documenta fifteen and 14. Biennial of Young Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Skopje. He has held lectures at Royal College of Art, Central Saint Martins, Haus der Elektronischen Künste, HDK Valand, Universität der Künste and Istanbul Modern. He is a member of Hœr NY, a feminist queer and bisexual lesbian art collective founded with Harley Aussoleil and Frances Breden.

The Climate of Art: The Conundrum of Sustainability

The art world is facing a problem: art itself is not sustainable. To be precise, what we consider as art does not contribute materially to a sustainable human existence within planetary ecology. As global warming unfolds all over the planet and while simultaneously art professionals seem increasingly willing to address our ecological role in the world, one cannot but notice an apparent futility in reducing the many aspects of the Anthropocene, e.g., resource extractivism and soil degradation, global commerce and trade routes, or energetic carbon-dependency and data-mining, to art’s content. Many artists are also activists in parallel to their creative work, yet often it appears as if both artists and curators remain content with works that merely “address” or “represent” climate change. Meanwhile, the Adornoian presumption of autonomous art persists—art ought not to do more than propose an aesthetic form for whichever content.

This conversation is particularly crucial in Switzerland as the upcoming cultural message (Kulturbotschaft)—a quadrennial set of guidelines informing all governmental cultural support in the country—is currently under consultation. The government’s draft dedicates a large section acknowledging that a cultural change is needed to contribute to a sustainable society,yet the course of action remains unclear. Besides a clear vision concerning architecture (Baukultur), the message limits itself to calling for a debate between funding bodies and institutions with the aim to reduce carbon emissions in cultural production. Simply put, this draft does not present a developed or convincing vision for a possible sustainable culture.

As a cultural event, foodculture days is not conceived with an explicitly political goal or position. Rather, the biennial functions as a platform for artists, designers, architects, chefs, and activists to present and discuss their work. It is a public forum, accompanied by the different kinds of pleasure food and gastronomy propose, for sustainable ecological and social relationships. This already is a provocation. Vevey, the city that hosts the event every two years, is home to the global headquarters of Nestlé, one of the largest food conglomerates worldwide and a controversial socio-political actor in the Global South.

This provocation is two-fold: the obvious one is by offering a platform for alternative perspectives on food, cooking, and care that defy this seemingly unavoidable corporate behemoth controlling worldwide food supply. Taking into account local cultures, social structures, and environmental challenges, cultural initiatives such as foodculture days counter the global experience of grocery shopping that make products traded and/or produced by a handful of Western companies inevitable. In this way, the artistic projects presented at foodculture days go beyond capitalist realism and the myth that only corporate techno-solutions may heal global ailments.

The second provocation runs deeper and confronts the traditional understanding of art in Switzerland. foodculture days outspokenly aims to overcome the traditional boundaries between contemporary art, performance, design, architecture, and food culture. Regardless of their field of practice, the participants come with an ideological aim, all sharing an interest in situating their practice in a determined context as well as in interacting with other participants and visitors of the biennial alike. Such interests are a decisive factor in the development of creative approaches that transcend traditional ideas of art, constituting the core of foodculture days’ program.

As a matter of fact, Nestlé itself ran a cultural foundation in Switzerland for many years, through which they supported cultural producers until 2022. Even though it never happened, it could have seemed natural for Nestlé to be interested in supporting a project like foodculture days. But, like most funding bodies in Switzerland, Nestlé’s cultural fund made a distinction between visual arts and other cultural formats. Nestlé’s specialty was its focus on providing instrumental support to non-institutional, often precarious exhibition spaces and cultural initiatives. Unsurprisingly, the projects they funded mostly catered to conservative notions of art that maintained the Adornoian autonomy of the artwork.

To be fair, most art funding in Switzerland relies on the same distinctions and the Nestlé foundation only represents a broadly accepted yet restrictive understanding of art. The experience of navigating artistic and cultural production in this country shows that the national foundation Pro Helvetia functions as a compass for other funding bodies and institutions: beyond technical tax and customs definitions, there is no official understanding of art or culture in Switzerland. What constitutes art is, instead, defined discursively through research and events. And, although Pro Helvetia is a forthcoming and responsive institution, when they support a project such as foodculture days they do so categorizing it not as “visual arts” but rather as “interdisciplinary”—a vaguely defined funding category.

The categorization of foodculture days as “interdisciplinary” is symptomatic of this general conservatism insofar as it preserves the autonomy of visual arts by offering this new, ad hoc vessel instead of adapting preexisting concepts to new practices. This raises the question of how trailblazing cultural institutions may become financially sustainable if public and private funding structures do not reflect their needs. Up to this day, the challenge of developing sustainable cultural formats and suitable funding structures is still up to the cultural initiators themselves.

The issue here is that the cultural innovation required for new sustainable art forms is not taking place within already established institutions. Admittedly, larger institutions and museums in Switzerland have taken up measures to reduce or mitigate their environmental impact and should be commended for doing so. For example, Swiss institutions optimize art handling and off-set flights. Some may even renovate, looking into alternative forms of insulation and heating. In some cases, art institutions have also programmed events and exhibitions that address or represent climate change, but these initiatives have yet to succeed in fundamentally transforming the cultural sector to make it structurally sustainable.

For such a change to happen, a necessary step would be to carefully reconsider the core business of these institutions, namely the definition of art itself. Every institution maintains such a definition that informs every aspect of its operation. A sustainable definition of art would, in other words, impact museum and exhibitory practices, notably by raising unprecedented questions such as to which end and how do we archive and conserve art? How can exhibitions respond to ecological processes rather than to cycles of attention? Are research and production possible without extractivist practices? And can sustainability be concretized otherwise than by merely representing climate change?

With its original focus and approach the foodculture days biennial manages to transcend naturalized ideas of autonomous art. In terms of sustainability, their main challenge is rather an infrastructural one: how to achieve long-term viability? With challenged access to structural funding and limited budgets, the success of a project like foodculture days remains reliant on significant personal commitment from the team year-round as well as unpaid labor from numerous volunteers to carry out decisive day-to-day tasks during the biennial. Though highly motivated, the people involved are objectively putting themselves at risk of exhaustion or burnout to meet expectations and achieve the ambitions of foodculture days. With an entire funding strategy to reinvent for each new edition, the perpetuation of such a project represents a Sisyphean task that constantly flirts with the personal limits of the people committed to its success.

After four editions but still without structural funding, the biennial has not yet developed its structural resilience. The current cultural funding scheme focusing on supporting one-off events appears like the main obstacle to durably establishing a new class of sustainable art projects. The biggest challenge for foodculture days henceforth is, therefore, its own institutionalization in order to develop long-term perspectives and cultural accountability. The biennial has already shaken things up by establishing a forum for sustainable cultural forms that does not adhere to autonomous terms of culture. If we are to develop an understanding of sustainable culture, for an art that is not beyond politics or the environment, then we must question the function of institutions themselves. We must now focus on cultivating ecological aesthesis: a sustainable understanding of art and thinking of art as inherently embedded in political and environmental processes. Only then will we have a base to create the institutional and economic structures needed for an ongoing transformation of our aesthetic climate.

Mateo Chacón Pino

Mateo Chacón Pino is a Colombian-Swiss art historian, curator and author. He has curated projects in art spaces, museums, galleries and farms in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany. He participated in The Curatorial and Artistic Thing at sixtyeight art institute in Copenhagen and in the Curatorial Programme at De Appel, Amsterdam. Mateo Chacón Pino currently lives in Kassel and works as a research assistant at the documenta Institute and at the University of Kassel at the Department of Art and Society, by Prof. Dr. Liliana Gómez. In his dissertation The Distinction of Art & Nature, he questions the epistemic time of art history in light of the Anthropocene and problematizes the notion of Contemporary Art in the context of the exhibition. He completed his master's thesis in 2021 at the University of Zurich on the role of governmental art funding for the understanding of art using the case study of the SüdKulturFonds of Switzerland.

The Climate of Art: The Conundrum of Sustainability

The art world is facing a problem: art itself is not sustainable. To be precise, what we consider as art does not contribute materially to a sustainable human existence within planetary ecology. As global warming unfolds all over the planet and while simultaneously art professionals seem increasingly willing to address our ecological role in the world, one cannot but notice an apparent futility in reducing the many aspects of the Anthropocene, e.g., resource extractivism and soil degradation, global commerce and trade routes, or energetic carbon-dependency and data-mining, to art’s content. Many artists are also activists in parallel to their creative work, yet often it appears as if both artists and curators remain content with works that merely “address” or “represent” climate change. Meanwhile, the Adornoian presumption of autonomous art persists—art ought not to do more than propose an aesthetic form for whichever content.

This conversation is particularly crucial in Switzerland as the upcoming cultural message (Kulturbotschaft)—a quadrennial set of guidelines informing all governmental cultural support in the country—is currently under consultation. The government’s draft dedicates a large section acknowledging that a cultural change is needed to contribute to a sustainable society,yet the course of action remains unclear. Besides a clear vision concerning architecture (Baukultur), the message limits itself to calling for a debate between funding bodies and institutions with the aim to reduce carbon emissions in cultural production. Simply put, this draft does not present a developed or convincing vision for a possible sustainable culture.

As a cultural event, foodculture days is not conceived with an explicitly political goal or position. Rather, the biennial functions as a platform for artists, designers, architects, chefs, and activists to present and discuss their work. It is a public forum, accompanied by the different kinds of pleasure food and gastronomy propose, for sustainable ecological and social relationships. This already is a provocation. Vevey, the city that hosts the event every two years, is home to the global headquarters of Nestlé, one of the largest food conglomerates worldwide and a controversial socio-political actor in the Global South.

This provocation is two-fold: the obvious one is by offering a platform for alternative perspectives on food, cooking, and care that defy this seemingly unavoidable corporate behemoth controlling worldwide food supply. Taking into account local cultures, social structures, and environmental challenges, cultural initiatives such as foodculture days counter the global experience of grocery shopping that make products traded and/or produced by a handful of Western companies inevitable. In this way, the artistic projects presented at foodculture days go beyond capitalist realism and the myth that only corporate techno-solutions may heal global ailments.

The second provocation runs deeper and confronts the traditional understanding of art in Switzerland. foodculture days outspokenly aims to overcome the traditional boundaries between contemporary art, performance, design, architecture, and food culture. Regardless of their field of practice, the participants come with an ideological aim, all sharing an interest in situating their practice in a determined context as well as in interacting with other participants and visitors of the biennial alike. Such interests are a decisive factor in the development of creative approaches that transcend traditional ideas of art, constituting the core of foodculture days’ program.

As a matter of fact, Nestlé itself ran a cultural foundation in Switzerland for many years, through which they supported cultural producers until 2022. Even though it never happened, it could have seemed natural for Nestlé to be interested in supporting a project like foodculture days. But, like most funding bodies in Switzerland, Nestlé’s cultural fund made a distinction between visual arts and other cultural formats. Nestlé’s specialty was its focus on providing instrumental support to non-institutional, often precarious exhibition spaces and cultural initiatives. Unsurprisingly, the projects they funded mostly catered to conservative notions of art that maintained the Adornoian autonomy of the artwork.

To be fair, most art funding in Switzerland relies on the same distinctions and the Nestlé foundation only represents a broadly accepted yet restrictive understanding of art. The experience of navigating artistic and cultural production in this country shows that the national foundation Pro Helvetia functions as a compass for other funding bodies and institutions: beyond technical tax and customs definitions, there is no official understanding of art or culture in Switzerland. What constitutes art is, instead, defined discursively through research and events. And, although Pro Helvetia is a forthcoming and responsive institution, when they support a project such as foodculture days they do so categorizing it not as “visual arts” but rather as “interdisciplinary”—a vaguely defined funding category.

The categorization of foodculture days as “interdisciplinary” is symptomatic of this general conservatism insofar as it preserves the autonomy of visual arts by offering this new, ad hoc vessel instead of adapting preexisting concepts to new practices. This raises the question of how trailblazing cultural institutions may become financially sustainable if public and private funding structures do not reflect their needs. Up to this day, the challenge of developing sustainable cultural formats and suitable funding structures is still up to the cultural initiators themselves.

The issue here is that the cultural innovation required for new sustainable art forms is not taking place within already established institutions. Admittedly, larger institutions and museums in Switzerland have taken up measures to reduce or mitigate their environmental impact and should be commended for doing so. For example, Swiss institutions optimize art handling and off-set flights. Some may even renovate, looking into alternative forms of insulation and heating. In some cases, art institutions have also programmed events and exhibitions that address or represent climate change, but these initiatives have yet to succeed in fundamentally transforming the cultural sector to make it structurally sustainable.

For such a change to happen, a necessary step would be to carefully reconsider the core business of these institutions, namely the definition of art itself. Every institution maintains such a definition that informs every aspect of its operation. A sustainable definition of art would, in other words, impact museum and exhibitory practices, notably by raising unprecedented questions such as to which end and how do we archive and conserve art? How can exhibitions respond to ecological processes rather than to cycles of attention? Are research and production possible without extractivist practices? And can sustainability be concretized otherwise than by merely representing climate change?

With its original focus and approach the foodculture days biennial manages to transcend naturalized ideas of autonomous art. In terms of sustainability, their main challenge is rather an infrastructural one: how to achieve long-term viability? With challenged access to structural funding and limited budgets, the success of a project like foodculture days remains reliant on significant personal commitment from the team year-round as well as unpaid labor from numerous volunteers to carry out decisive day-to-day tasks during the biennial. Though highly motivated, the people involved are objectively putting themselves at risk of exhaustion or burnout to meet expectations and achieve the ambitions of foodculture days. With an entire funding strategy to reinvent for each new edition, the perpetuation of such a project represents a Sisyphean task that constantly flirts with the personal limits of the people committed to its success.

After four editions but still without structural funding, the biennial has not yet developed its structural resilience. The current cultural funding scheme focusing on supporting one-off events appears like the main obstacle to durably establishing a new class of sustainable art projects. The biggest challenge for foodculture days henceforth is, therefore, its own institutionalization in order to develop long-term perspectives and cultural accountability. The biennial has already shaken things up by establishing a forum for sustainable cultural forms that does not adhere to autonomous terms of culture. If we are to develop an understanding of sustainable culture, for an art that is not beyond politics or the environment, then we must question the function of institutions themselves. We must now focus on cultivating ecological aesthesis: a sustainable understanding of art and thinking of art as inherently embedded in political and environmental processes. Only then will we have a base to create the institutional and economic structures needed for an ongoing transformation of our aesthetic climate.

Mateo Chacón Pino

Mateo Chacón Pino is a Colombian-Swiss art historian, curator and author. He has curated projects in art spaces, museums, galleries and farms in Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany. He participated in The Curatorial and Artistic Thing at sixtyeight art institute in Copenhagen and in the Curatorial Programme at De Appel, Amsterdam. Mateo Chacón Pino currently lives in Kassel and works as a research assistant at the documenta Institute and at the University of Kassel at the Department of Art and Society, by Prof. Dr. Liliana Gómez. In his dissertation The Distinction of Art & Nature, he questions the epistemic time of art history in light of the Anthropocene and problematizes the notion of Contemporary Art in the context of the exhibition. He completed his master's thesis in 2021 at the University of Zurich on the role of governmental art funding for the understanding of art using the case study of the SüdKulturFonds of Switzerland.